The String of Precious Jewels

The String of Precious Jewels

A Classical Summary of Buddhist Ethics

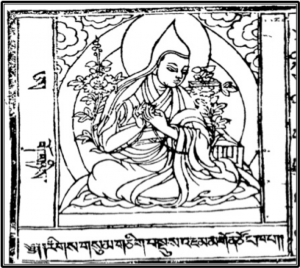

written by Gyal Kenpo, Drakpa Gyeltsen (1762–1837)

translated by Alison Zhou

with Geshe Michael Roach

Copyright © 2018 individually by Alison Zhou & Geshe Michael Roach.

All rights reserved.

Sections may be reproduced with the author’s permission. Please contact:

alisonzhouxiaoping@gmail.com

Volume 73 of the Diamond Cutter Classics Series

Diamond Cutter Press

6490 Arizona Route 179A

Sedona, Arizona 86351

USA

Table of Contents

The String of Precious Jewels:

A Brief Word-by-Word Commentary on Je Tsongkapa’s

“Essence of the Ocean of Vowed Morality”……………………………………… 5

An offering of praise, and a promise…………………………………………………………. 5

An expression of auspiciousness………………………………………………………………. 7

Je Tsongkapa’s offering of praise…………………………………………………………….. 10

The greatness of the vows of freedom……………………………………………………… 12

An overview of the vows………………………………………………………………………… 15

Je Tsongkapa’s pledge to compose the work…………………………………………… 16

The basic nature of the vows of freedom…………………………………………………. 17

Viewpoint shared by both the Sutrist and Detailist Schools…………………….. 17

Unique positions of the two schools………………………………………………………… 19

Divisions of the vows………………………………………………………………………………. 21

How the vows can be grouped………………………………………………………………… 22

The content of each of the sets of vows……………………………………………………. 24

The one-day vow…………………………………………………………………………………….. 24

The root four types of behavior from which we refrain…………………………… 25

The secondary four types of behavior from which we refrain…………………. 28

How the one-day vow is taken………………………………………………………………… 30

The basic nature of the lifetime layperson’s vow…………………………………….. 31

The different divisions of the lifetime layperson’s vow…………………………… 33

Vows of a novice monk or nun………………………………………………………………… 35

How we arrive at six secondary components for the novice vow……………. 36

How we arrive at thirteen commitments for a novice……………………………… 37

The ceremony for ordaining a novice…………………………………………………………..

Je Tsongkapa’s Root Text:

The Essence of the Ocean of Vowed Morality………………………………….. 38

Appendices…………………………………………………………………………. 45

Comparative list of the names of divine beings & places………………………… 46

Bibliography of works originally written in Sanskrit………………………………. 47

Bibliography of works originally written in Tibetan……………………………….. 48

The String of Precious Jewels

[1]

[folio 1a]

,’DUL BA RGYA MTSO’I SNYING PO BSDUS PA’I TSIG ‘GREL RIN CHEN PHRENG BA ZHES BYA BA BZHUGS SO,,

Herein lies The String of Precious Jewels: A Brief Word-by-Word Commentary on Je Tsongkapa’s “Essence of the Ocean of Vowed Morality.”

[2]

SARBA MANGGA LAm,,

Sarva mangalam!

May goodness ever prevail!

An offering of praise, and a promise

[3]

[f. 1b]

,GZUGS SKU’I LHUN POR MTSAN DPE’I BANG RIM MDZES,

,CHOS SKU’I MKHYEN BRTZE NYI ZLA’I ‘OD ZER SPRO,

,PHAN DANG BDE BA’I RIN CHEN GTER GYUR PA,

,THUB DBANG RGYA MTSO CHE LA GUS PHYAG ‘TSAL,

I bow with respect to the ocean

Of the Lords of the Victors:

A vast treasure of jewels of help and happiness,

Whose physical bodies are the great

Central mountain of the world

With its terraces of signs and marks;

And whose body of reality

Shines in the light of sun and moon:

Their knowledge, and their love.[1]

[4]

,’DUL GZHUNG ‘BUM SDE ‘CHAD MKHAS BLO GROS ‘OD,

,BZANG PO’I GRAGS SNYAN KHOR YUG KUN GSAL MA’I,

,KHONG BA LAS BRGAL SMRA BA’I NYI MA CHE,

,’JAM MGON TZONG KHA PA DE SPYI BOS MCHOD,

I bow and touch the top of my head

To the feet of Je Tsongkapa, the gentle protector.

You are a master at explaining t

he massive collection

Of the classics of Buddhist ethics;

You are that great sun among all teachers,

And the light of your wisdom and resplendent fame

Covers the entire world

All the way to the surrounding mountains.[2]

[5]

,RGYA BOD MKHAS PA’I CHOS ‘DUL KUN BZUNG NAS,

,LEGS BSHAD RIN CHEN DBYIG GI CHAR ‘BEBS SHING,

,GTAN BDE THAR PA’I LAM STON BKA’ DRIN CAN,

,KUN MKHYEN BZHAD PA’I RDO RJER PHYAG BYAS TE,

I bow down to the all-knowing Shepay Dorje,[3]

Who mastered all the teachings

On Buddhist ethics given by masters

Of the lands of India and Tibet;

He then let fall a gentle rain

Of the priceless jewels of his fine explanation,

And in his kindness showed to us

The path to freedom—ultimate happiness.

[6]

,GANGS CAN MKHAS KUN MGO SKYES LAN BU’I RTZER [f. 2a],

,

ZHABS SEN RIN CHEN NGAL GSO TZONG KHA PAS,

,LEGS GSUNG ‘DUL BA RGYA MTSO’I SNYING PO YI,

,TSIG ‘GREL RIN CHEN PHRENG BA DENG ‘DIR ‘CHAD,

I will now teach you the String of Precious Jewels,

A commentary upon the wording

Of the Essence of the Ocean of Vowed Morality—

That brilliant teaching by Tsongkapa,

Who stands easily head and shoulders

Above all the other sages in this Land of Snows.

An expression of auspiciousness

[7]

` ,DE LA ‘DIR RJE THAMS CAD MKHYEN PA MTSAN BRJOD PAR DKA’ BA BLO BZANG GRAGS PA’I DPAL ZHES MTSAN SNYAN RNGA PO {%BO} CHE’I SGRA DBYANGS KHAMS GSUM GYI ‘GRO BA’I RNA BA’I RGYAN DU GYUR PA

There is a Lama, the Lord, the one who knows all things. And I say his name only in whispered awe: the glorious Lobsang Drakpa. The roar of that drum—the fame of his name—has reached the ears of beings living throughout all three realms of the universe.[4]

[8]

DE NYID KYIS BSTAN PA’I RTZA BA DAM PA’I CHOS ‘DUL BA’I GSUNG RAB THAMS CAD KYI BRJOD BYA YONGS SU RDZOGS PA’I SNYING PO BSDUS TE STON PA

This Lama has taught us the brief essence of the entire content of all the high instructions which are the very root of the teachings of the Buddha; that is, the teachings on vowed morality.

[9]

TSIG DON PHUN SUM TSOGS PA’I BSTAN BCOS ‘DUL BA RGYA MTSO’I SNYING PO BSDUS PA ZHES BYA BA MDZAD PA GANG YIN PA DE NI GANG BSHAD PAR BYA BA’I CHOS SO,,

The name of the work he wrote—a classical commentary which is perfect in both its wording and its meaning—is The Brief Essence of the Ocean of Vowed Morality. And it is that text which I shall explain here.

[10]

DES NA ‘DI LA GSUM, SHIS BRJOD SNGON DU [f 2b] BTANG NAS MCHOD PAR BRJOD PA, GZHUNG DNGOS BSHAD PA, BRTZAMS PA MTHAR PHYIN PA’I BYA BA’O,,

I will proceed in three steps: an explanation of the offering of praise, preceded as it is by an expression of auspiciousness; a commentary upon the actual text itself; and then some words about the final section, which completes the composition.

[11]

DANG PO LA GNYIS, GNAS SKABS DANG MTHAR THUG GI DON LA SHIS PA BRJOD PA DANG, SNGON GYI BKAS BCAD DANG MTHUN PAR MCHOD PAR BRJOD PA’O,,

The first of these has two parts: an expression of auspiciousness to help us reach our immediate and ultimate goals; and then the offering of praise, respecting the decree of the kings of yore.

[12]

DANG PO NI,

The first, the expression of auspiciousness, is presented in the following line from the root text:

[13]

AOm BDE LEGS SU GYUR CIG

Om! May there be happiness and goodness.[5]

[14]

,CES GSUNGS TE DON NI AOm NI BKRA SHIS PA’I TSIG YIN NO,

As for the meaning of this opening, the syllable om is an expression of auspiciousness.

[15]

JI SKAD DU,

,AOm NI CI ZHIG YIN PAR BRJOD,

,MCHOG DANG NOR STER DPAL DANG G-YANG,

,DAM BCA’ BA DANG BKRA SHIS DON,

,NOR BU ‘DZIN PA’I SNGAGS SU BRJOD,

,CES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR RO,,

Because as they say:

What is om? I will tell you what it is.

Om can refer to giving the highest of goals,

Or else wealth, or glory, or fortune;

It can also have the meaning

Of making a pledge, [6] or of auspiciousness.

This is the mantra

Of the One Who Holds the Jewel.[7]

[16]

BDE LEGS SU GYUR CIG CES PA GNAS SKABS DANG MTHAR THUG GI ‘DOD DON THAMS CAD BDE LEGS SU STE BDE BLAG NYID DU ‘GRUNG BAR {%’GRUB PAR} GYUR CIG CES SHIS PAR BRJOD PA’O,

The phrase May there be happiness and goodness is an expression of auspiciousness which means: May every being achieve all their wishes—both temporal and ultimate—in a “good and happy way,” meaning “with perfect ease.”

Je Tsongkapa’s offering of praise

[18]

THAMS CAD MKHYEN PA LA PHYAG ‘TSAL LO

I bow down to the Omniscient One.

[19]

ZHES PA STE BSLAB PA’I GNAS RNAMS LA BCAS PA MDZAD PA PO THAMS CAD MKHYEN PA SANGS RGYAS NYAG GCIG YIN GYIS {%GYI?} GZHAN DAG NI BLANG DOR GYI GNAS CHES PHRA BA LA MNGON SUM GYIS GZIGS PA MI ‘JUG PA’I PHYIR BCAS PA MDZAD PA POR MI RUNG BAS NA

It is only the Omniscient One, the Buddha, who can decide upon new additions to the rules of conduct. Other people lack the ability to see, directly, into the most subtle points of what kind of behavior is good to follow, and what behavior should be avoided; as such, they are not suitable to be the ones who make these kinds of decisions.

[20]

JI LTA JI SNYED KYI RNAM PA MA LUS PAR MKHYEN PA DE LA PHYAG ‘TSAL LO ZHES PA STE, DE NI SNGON GYI CHOS RGYAL LO PAn DAG GI BKAS BCAD DANG MTHUN PAR MDZAD PA’O,

And so Je Tsongkapa is here bowing down to the one who knows all the things in the universe—and who simultaneously knows how all these things are.[10] He is also acting in accordance with the decree made in times of old, by the dharma kings, master translators, and sages.[11]

The greatness of the vows of freedom

[21]

GNYIS PA GZHUNG DNGOS BSHAD PA LA GNYIS, LUS MDOR BSTAN GYI SGO NAS BSHAD PAR DAM BCA’ BA DANG, YAN LAG RGYAS PAR BSHAD PA’O,,

The second step, which is an explanation of the actual text, has two parts: explaining the pledge to compose the text, which is done by summarizing the entire work; and explaining all the components in more detail.

[22]

DANG PO LA GSUM, BRJOD BYA SO THAR GYI SDOM PA’I CHE BA BSTAN PA DANG, CHE BA [f. 3a] DE DANG LDAN PA’I SO THAR GYI SDOM PA’I LUS RNAM PAR BZHAG PA, DAM BCA’ BA DNGOS SO, ,DANG PO NI,

The first of the two parts has three sections: demonstrating the greatness of the vows of freedom, which are the subject of the book; giving an overview of the vows which possess this greatness; and then finally the actual pledge. Here is the first.

[23]

,GANG LA BRTEN NAS BDE BLAG TU,

,THAR PA’I GRONG DU BGROD PA’I THABS,

,BDE GSHEGS BSTAN PA’I SNYING PO MCHOG

,SO SOR THAR CES GRAGS PA GANG,

(1)

There is something which, if you rely on it,

Is the way to travel with ease to the city of freedom;

The supreme essence of the teachings of those Gone to Bliss;

It is that which is known as “individual freedom.”

[24]

,ZHES GSUNGS TE THABS GANG LA BRTEN NAS BDE BLAG TU‘AM TSEG CHUNG NGU’I SGO NAS LAS NYON GYIS ‘KHOR BAR DBANG MED DU ‘CHING BA LAS GROL BA’I THAR PA’I GRONG KHYER DU BGROD PAR BYED PA’I THABS ZAB MO DANG, RGYU MTSAN DE NYID KYI PHYIR BDE BAR GSHEGS PA’I BSTAN PA’I SNYING PO MCHOG TU GYUR PA NI,

Now there is a profound method which—if you rely on it—can help you travel with ease (meaning, without much trouble) to the city of freedom, where you are liberated from being chained, helplessly, to this cycle of pain by karma and negative emotions. And for this very reason, that method is the supreme essence of the teachings of Those Who Have Gone to Bliss.[12]

[25]

SO SOR THAR PA’I SDOM PA ZHES YONGS SU GRAGS PA GANG YIN PA DE NYID YIN TE RGYU MTSAN GANG GIS ZHEN {%ZHE NA} ‘DI LTAR SRID PA’I RTZA BA BDAG ‘DZIN DRUNG NAS ‘BYIN PA’I SHES RAB LHAG MTHONG

And this method is none other than that which is widely known as “the vows of individual freedom.”[13] And why is that? It is because we seek to develop, within our hearts, deep insight; meaning the wisdom which can rip out, from its roots, the tendency to hold on to some self-nature to things—a tendency which is the very root of suffering life.

[26]

RGYUD LA SKYE BA LA SEMS BYING RGOD KYI NYES PAS BSKYOD PAR MI NUS PA’I TING NGE ‘DZIN ZHI GNAS SNGON DU ‘GRO DGOS SHING

To develop this wisdom, we must first attain quietude; meaning a state of meditation so strong that our mind can no longer be shaken by the interruptions to meditation known as “dullness” and “agitation.”

[27]

DE’I RTZA BA NYON MONGS PA’I MGO GNON PA’I GNYEN POR LUS NGAG GI NYES SBYONG {%SPYOD} LAS LDOG PA’I TSUL KHRIMS YONGS SU DAG PA MED MI RUNG DU DGOS PA’I PHYIR RO,,

The very root of this strength is to observe a very pure form of ethical behavior, where we turn away from negative deeds in our actions and our words. This acts as an antidote which suppresses everything related to our negative emotions. As such, this ethical behavior is something that we absolutely cannot do without.

[28]

DES PHYIR RGYAL BA’I LUNG GI BSTAN PA SDE SNOD GSUM DANG, RTOGS PA’I BSTAN PA BSLAB PA GSUM DU ‘DU TSUL LEGS PAR KHONG DU CHUD NA SO SOR THAR PA’I SDOM PA SANGS RGYAS KYI BSTAN PA’I SNYING PO MCHOG TU NGES PA RNYED PAR ‘GYUR RO,

Now the teachings of the Victors consist of the physical teachings—the three collections of scripture; and the teachings as ideas—referring to the three trainings.[14] If you understand thus the place that an ethical life holds within these two forms of the teachings, then you can come to a true perception that the vows of individual freedom are indeed the supreme essence of the teachings of the Buddhas.

An overview of the vows

[29]

` ,GNYIS PA CHE BA DE DANG LDAN PA’I SO THAR GYI SDOM PA’I LUS RNAM PAR BZHAG PA NI,

Here secondly is an overview of the vows which possess the greatness just described.

[30]

,NGO BO DANG NI RAB DBYE DANG,

,SO SO’I NGOS ‘DZIN SKYE BA’I RTEN,

,GTONG [f. 3b] BA’I CHA {%RGYU} DANG PHAN YON TE,

,RNAM PA DRUG

,CES GSUNGS TE,

(2b)

…Six categories:

Their basic nature, the way they are divided,

Their individual descriptions, who can take them,

How they are lost,[15] and the benefits they give.

[31]

SO THAR GYI SDOM PA’I NGO BO JI LTAR YIN PA DANG NI, DE’I RAB TU DBYE BA CI TZAM YIN PA DANG, PHYE BA SO SO’I NGOS ‘DZIN TSUL DANG, SDOM PA DE DAG ‘GRO BA GANG DANG GANG ZAG JI LTA LTA BU {%JI LTA BU} LA SKYE BAR ‘GYUR BA SKYE BA’I RTEN DANG, GANG BYUNG NA SDOM PA DE DAG GTONG BAR ‘GYUR BA’I GTONG BA’I CHA {%RGYU} DANG, PHAN YON GANG ZHIG ‘BYUNG BA’I TSUL TE, DON RNAM PA DRUG GO ZHES SO,,

The vows of individual freedom can be summarized in keeping with six major subject categories: (1) a description of their basic nature; (2) the way in which they are divided; (3) the description of each individual division; (4) what kind of being, and what kind of person, can take them (that is, the kind of individual in whom these vows can take root); (5) how they are lost (meaning, the kind of circumstances in which the vows can be lost); and (6) the benefits the vows give when they are honored.

[32]

‘DI NI GZHUNG GI BRJOD BYA’I LUS YONGS SU RDZOGS PA’I SDOM MO,

This is a summary, in verse, of the entire body of the text—all of its topics.

Je Tsongkapa’s pledge to compose the work

[33]

GSUM PA DAM BCA’ BA NI

Here is our third point from above, which is Je Rinoche’s own pledge to compose his work. We find it in the following part of a line here from the root text:

[34]

GIS JI BZHIN BSHAD

(2a)

In keeping, I shall explain them in…

[35]

CES GSUNGS TE DE LTAR DON TSAN DRUG GIS SO THAR GYI SDOM PA’I RNAM BZHAG ‘DUL BA’I MDO DANG DGONGS ‘GREL TSAD LDAN DAG GI DGONGS PA JI LTA BA BZHIN DU BLO BZANG GRAGS PA BDAG GIS BSHAD PAR BYA’O, ,ZHES PA’O,,

The third section, Je Tsongkapa’s pledge to compose his work, is indicated in the wording, “I shall explain them, in keeping, with the six.” What this is saying is: “I, Lobsang Drakpa,[16] shall make a presentation of the vows of individual freedom by means of six different topics, and in keeping with the true thought of the Sutra on Vowed Morality,[17] and authoritative commentaries upon its own intent.”

The basic nature of vows of freedom

[36]

GNYIS PA YAN LAG RGYAS PAR BSHAD PA LA SNGAR LTAR DRUG LAS DANG PO SDOM PA’I NGO BO LA, MDO SDE BA {%PA} DANG BYE BRAG SMRA BA GNYIS KA’I THUN MONG GI ‘DOD PA DANG, SO SO’I THUN MONG MA YIN PA’I ‘DOD PA BRJOD PA GNYIS LAS, DANG PO NI,

Here we begin our more

detailed explanation of these various components. As mentioned before, there are six; and we will cover the first of them in two steps: a description of the position shared by the Sutrist and Detailist Schools;[18] and then a description of unique positions held by each of these two. Here is the first.

Viewpoint shared by both the Sutrist and Detailist Schools

[37]

,NGES ‘BYUNG BSAM BAS {%PAS} RGYU BYAS NAS,

,GZHAN GNOD GZHI DANG BCAS PA LAS,

,LDOG PA

ZHES GSUNGS TE,

(3)

It is a turning away from harming others,

And its basis, caused by an attitude

Of renunciation.[19]

[38]

SO THAR GYI SDOM PA’I NGO BO NI, SDUG BSNGAL GYIS YID SUN TE DE LAS GROL BA’I THAR PA DON DU GNYER BA’I NGES ‘BYUNG GI BSAM PA BCOS MA YAN CHAD KYIS RGYU BYAS PA TE DES KUN NAS BSLANGS TE, SEMS CAN GZHAN LA GNOD PA GZHI DANG BCAS PA LAS LDOG PA‘I DGE BA’I LAS ZHIG GO

What is the basic nature of a vow of individual freedom? It is the virtuous action of turning away from harming any other living being, and its basis. And this good action is caused by—motivated by—an attitude of renunciation which is at least contrived (and hopefully more); and where we aspire to be free of the trouble of life’s pain.

[39]

,DE NI SDE BA {%PA} GONG ‘OG GNYIS [f. 4a] KA ‘DOD DO,,

This position on the basic nature of these vows is accepted by both the higher and lower schools.[20]

[40]

‘DIR GZHAN LA GNOD PA GZHI DANG BCAS PA ZHES GSUNGS PA’I GNOD PA NI TSANGS SPYOD LA GNOD PA MI TSANGS SPYOD, LONGS SPYOD LA GNOD PA MA BYIN LEN, SROG LA GNOD PA SROG GCOD, DON ‘GRUB PA LA GNOD PA RDZUN DU SMRA BA STE

Now, what is the harm in harming others, and its basis? What harms our sexual purity is improper sexual behavior; what harms our possessions is stealing; what harms our life is killing; and what harms our accomplishing what we hope to is lying.

[41]

‘DI BZHI GNOD PA’I RGYU DNGOS DANG, PHYI DRO’I KHA ZAS SOGS YAN LAG GZHAN RNAMS GNOD PA DE DAG ‘BYUNG BA’I GZHI YIN PA’I PHYIR GZHI ZHES BSHAD DO,,

These four are direct causes of harm. But other components—such as a monk or nun breaking the ordained person’s vow against eating after noon—act as a basis or foundation for the other harms to occur; this is why the root text mentions “and its basis.”[21]

Unique positions of the two schools

[42]

GNYIS PA NI,

This brings us to our description of the unique positions held by each of these two schools: the Sutrist and the Detailist. It is described in Je Tsongkapa’s next verse:

[43]

,DE YANG LUS GA {%NGAG} LAS,

,GZUGS CAN YIN ZHES ‘DOD PA DANG,

,SPONG BA’I SEMS PA RGYUN CHAGS PA,

,SA BON DANG BCAS YIN NO ZHES,

,’DOD PA’I TSUL NI RNAM PA GNYIS,

,RANG GI SDE PA GONG ‘OG SMRA,

,ZHES GSUNGS TE,

(4)

It is physical and verbal karma

Which they assert is physical matter.

The others say it is the intention to give up

And its seed as it continues in your mind.

Thus our schools’ positions are two:

What the higher and lower assert.

[44]

BSHAD MA THAG PA’I SO THAR GYI SDOM PA’I NGO BO NI DGE BA’I LAS TE, DE YANG LUS NGAG GI LAS SU GYUR PA RNAM PAR RIG BYED DANG RNAM PAR RIG BYED MA YIN PA’I GZUGS KYIS BSDUS PA’I GZUGS CAN YIN ZHES ‘DOD PA DANG,

These schools have two different positions here. One says that the essential nature of one of the vows of individual liberation which we’ve just listed is that it is good deed; and they also assert that such a vow consists of either physical or verbal karma—something which is physical matter, included either into communicating form or non-communicating form.[22]

[45]

YANG LUS NGAG GI LAS SU GYUR PA RANG GI MI MTHUN PHYOGS SPANGS PA’I SEMS PA RGYUN CHAGS PA SA BON DANG BCAS PA YIN NO ZHES ‘DOD PA’I TSUL NI RNAM PA GNYIS YOD CING,

The second position is that a vow of individual freedom consists of the intention to give up what works against the vow—negative actions of body and speech; this intention is counted along with its seed, as it—the intention—continues in your mind.

[46]

PHYI MA NI MDO SDE PA DANG SNGA MA NI BYE BRAG SMRA BA’I BZHED PA STE RANG GI SDE PA GONG ‘OG GNYIS KYIS DE LTAR SMRA‘O, ,ZHES PA’O,,

The latter position is the one accepted by the Sutrists, and the former is that followed by the Detailists; thus we can say that this is what the two of our higher and lower schools assert.[23]

Divisions of the vows

[47]

GNYIS PA DE’I RAB TU DBYE BA LA GNYIS, DBYE BA DNGOS DANG, BSDU TSUL LO, ,DANG PO NI,

This brings us to the second of the six subject categories from above: an explanation of the way in which the vows are divided. We proceed in two steps: the actual divisions, and then ways in which the vows are grouped. The first is described in the following verse.

[48]

,BSNYEN GNAS DGE BSNYEN PHA MA DANG,

,DGE TSUL PHA MA DGE SLOB MA,

,DGE SLONG MA DANG DGE SLONG [f. 4b]

STE,

,SO SOR THAR PA RIGS BRGYAD DO,

,ZHES GSUNGS TE,

(5)

There are eight different classes

For the vows of individual freedom:

The one-day vow; male and female layperson vows;

Male and female novice vows;

Intermediate nun’s vows; and the vows

Of a fully ordained nun or monk.

[49]

BSNYEN GNAS DANG DGE BSNYEN PHA MA GNYIS DANG, DGE TSUL PHA MA GNYIS DANG DGE SLOB MA DANG, DGE SLONG MA DANG, DGE SLONG PHA STE SO SOR THAR PA‘I SDOM PA LA RIGS BRGYAD YOD DO ZHES SO,,

What this verse is saying is that there are eight different classes for the different vows of individual freedom: these are the one-day vow; the two of male and female lifetime layperson vows; the two of male and female novice vows; the one set of vows for an intermediate nun; and the vows of a female and a male person with full ordination.

How the vows can be grouped

[50]

GNYIS PA BSDU TSUL NI,

Our second point, on how the vows can be grouped, is presented in the next lines of Tsongkapa’s root text:

[51]

,KHYIM PA’I SDOM PA DANG PO GSUM,

,RAB BYUNG SDOM PA THA MA LNGA,

,ZHES GSUNGS TE

(6)

The first three vows are for laypeople,

The last five vows for the ordained.

[52]

RIGS BRGYAD PO DE DAG BSDU NA, KHYIM PA’I PHYOGS KYI SDOM PA’I NANG DU BSNYEN GNAS DGE BSNYEN PHA MA’I SDOM PA STE SDOM PA DANG PO GSUM ‘DU ZHING, RAB BYUNG GI PHYOGS KYI SDOM PA’I NANG DU DGE TSUL PHA MA GNYIS DANG, DGE SLOB MA DANG, DGE SLONG PHA MA’I SDOM PA GNYIS TE SDOM PA THA MA LNGA ‘DU’O,,

These eight types of vows can be organized into two different groups. First there are the vows meant for laypeople; this group consists of the first three sets of vows: the one-day vows; and the lifetime layperson vows for a male or a female. And then there are the vows meant for people who are ordained; this group consists of the last five sets of vows: the two sets for a male or female novice; the vows of an intermediate nun; and the two sets for a fully ordained monk or nun.

[53]

GZHAN YANG RDZAS RIGS KYI SGO NAS BSDU NA DGE BSNYEN PHA MA’I SDOM PA RDZAS GCIG ,DGE TSUL PHA MA GNYIS DANG, DGE SLOB MA’I SDOM PA GSUM RDZAS GCIG ,DGE SLONG PHA MA’I SDOM PA RDZAS GCIG ,BSNYEN GNAS KYI SDOM PA LOGS SU RDZAS GCIG STE RDZAS KYI SGO NAS BZHIR ‘DU’O,

The different types of vows can also be grouped according to the type of content. The lifetime lay vows for a male or a female are then grouped together, by type of content; the three vows of a male or female novice, along with the intermediate nun’s vows, are similarly grouped together; the vows of a male or female with full ordination are thus grouped; and finally the one-day vows are grouped separately by content—which makes for a total of four different groups, by type of content.

[54]

` ,DUS KYI SGO NAS BSDU NA BSNYEN GNAS KYI SDOM PA NYIN ZHAG GI MTHA’ CAN DANG, GZHAN BDUN JI SRID ‘TSO’I MTHA’ CAN YIN PAS GNYIS SU ‘DU’O,,

The vows can also be grouped by their duration, in which case there are but two groups: the one-day vow expires at the end of a single 24 hour period; and then the other seven sets of vows expire only at the end of the time for which one lives in this life.

[55]

YAN LAG GI SGO NAS DGE SLONG PHA MA’I SDOM PA NI LUS NGAG GI MI DGE BDUN PO SDER GTOGS DANG BCAS PA THAMS CAD LAS LOG PA YIN LA, DE LAS GZHAN PA’I DRUG PO RNAMS LA NI LUS KYIS SROG GCOD SOGS GSUM DANG NGAG GIS RDZUN SMRA BA DANG BZHI SDER GTOGS DANG [f. 5a] BCAS PA LAS LOG PA STE GNYIS SU ‘DU’O,,

We can also group these different types of vows into two, according to their components. The vows for a fully ordained male or female involve refraining from the entire group of the seven bad deeds of body and speech, along with everything else related to them. The six remaining types of vows involve refraining from the three we commit physically—killing and the other two—as well as from, verbally, telling lies; along with everything else related to them.

The content of each of the sets of vows

[56]

GSUM PA PHYE BA SO SO’I NGOS ‘DZIN LA LNGA LAS, DANG PO BSNYEN GNAS KYI SDOM PA NI,

This brings us to the third of our six subject categories: identifying the content of each of the different sets of vows. Here there are five sections, beginning with the one-day vow.

The one-day vow

[57]

,RTZA BA BZHI DANG YAN LAG BZHI,

,BRGYAD SPONG BSNYEN GNAS SDOM PA’O,

ZHES GSUNGS TE,

(7)

The one-day vow is to give up eight:

The root four and the secondary four.

[58]

SPANG BYA RTZA BA BZHI DANG YAN LAG BZHI STE BRGYAD SPONG ZHING LUS NGAG GIS SLAR LDOG PA’I RAB TU PHYE BAS NYIN ZHAG GI MTHA’ CAN GYI SDOM PA DE NI BSNYEN GNAS KYI SDOM PA’O,,

The one-day vow is characterized by giving up—that is refraining from, in both our physical actions and our verbal expressions—eight different undesirable actions: the root four, and the secondary four. And it expires after a single 24-hour period.

The root four types of behavior

from which we refrain

[59]

SPANG BYA BRGYAD PO DE LAS RTZA BA BZHI STON PA’I PHYIR,

The next lines of the root text explain for us which—of the eight kinds of behavior we give up here—are considered the “root four.”

[60]

,MI TSANGS SPYOD DANG MA BYIN LEN,

,SROG GCOD RDZUN TU SMRA BA RNAMS,

,RTZA BA BZHI YIN,

ZHES GSUNGS TE,

(8)

The root four are sexual activity,

Stealing, killing, and speaking lies.

[61]

BDE BA MYONG ‘DOD KYIS KUN NAS BSLANGS STE RANG GZHAN GYIS {%GYI, see second quotation below} RMA’I SGO GSUM GANG RUNG DU RANG NYID KYIS {%KYI?} NOR BU BCUG PAS BDE BA NYAMS SU MYONG BA MI TSANGS SPYOD DANG,

The first thing we refrain from here is any kind of sexual activity. This activity is where—out of an intention where we desire to experience pleasure—we insert our “jewel” into any one or more of the three “open wounds,” and by so doing have an experience of pleasure.[24]

[62]

RDZAS THOB ‘DOD KYIS KUN NAS BSLANGS TE GZHAN GYIS BDAG TU BZUNG BA’I RDZAS RIN THANG LONGS PA BRKUS PA DANG ‘PHROG PA RDZAS SNGAGS KYI NUS PAS ‘GUG PA SOGS THABS GANG YANG RUNG BA’I SGO NAS RDZAS TE {%DE} PHA ROL PO DANG ‘BRAL BAR BYAS TE RANG GIS THOB BLO SKYES PA MA BYIN LEN DANG,

Now what is stealing? First we must have a motivation to obtain a certain object; that object must be considered their own by another person, and it must be of sufficient value. And to obtain it, we engage in some kind of means—be it theft in stealth; or outright robbery; or some kind of magic spell or substance that brings the thing to us. In any case, when the object is removed from the other person, and we finally consider it our own, then we have committed stealing.

[63]

SROG GCOD ‘DOD KYIS KUN NAS BSLANGS TE MI’I ‘GRO BA DNGOS DANG THA NA MNGAL GYI GNAS SKABS KYANG RUNG DE DANG DE’I SROG DBANG ‘GAG PA’I THABS GANG YANG RUNG BA’I SGO NAS RANG GI SNGA ROL TU GANG ZAG TE SHI BAR BYAS PA SROG GCOD DANG,

And what here is it to kill? First, we must have the intention to take a life—whether it be an actual full-grown human, or on down to a fetus in the womb. We undertake any method at all to stop its life; and we cause this person to die, before we do. Then we have committed, in this context, the act of killing.

[64]

RDZUN SMRA ‘DOD KYIS KUN NAS BSLANGS TE BSAM GTAN GZUGS MED KYI TING NGE ‘DZIN DANG MNGON SHES RDZU ‘PHRUL SOGS RANG NYID KYIS MA THOB [f.5b] BZHIN DU THOB PAR KHAS LEN PA DANG,

What, in this vow, is it to speak a lie? First we must intend to lie; and then for example we claim to others that we have attained (even though in truth we have not) something like the deep meditation states of the concentration levels, or the levels of formless-realm focus. Or perhaps we make the same claim about having gained powers such as clairvoyance, or the ability to perform miracles.

[65]

LHA LA SOGS PA’I ‘GRO BA GZHAN MA MTHONG BZHIN DU MTHONG BAR KHAS LEN PA SOGS MI GZHAN DAG LAS CHES KHYAD PAR DU ‘PHAGS PA’I CHOS RANG LA MED BZHIN DU YOD PAR SMRA BAS RDZUN TU SMRA BA STE ‘DI DAG RNAMS NI RTZA BA BZHI YIN NO ZHES SO,,

Or perhaps we claim, without having done it, that we have seen divine beings or the like. In short, we say that we have reached qualities that are far beyond those of other people—even though we haven’t. This then is what it is to lie in this vow; and all four of these taken together are referred to as the “root four.”

[66]

‘DI LAS GZHAN PA’I SROG CHAGS GZHAN GSOD PA DANG, RDZAS PHRA MO RKU BA DANG, DON MED PAR {Sw: i.e. not correct; not “meaningless”} RDZUN TSIG SMRA BA DE DAG KYANG KHA NA MA THO BA YIN PAS SPANGS DGOS SO,,

Other forms of these deeds—for example, killing forms of life other than the human form mentioned here; or stealing types of things other than those described here; or lies about other things, telling mistruths about them—are still actions that wise people refrain from, and we must as well.[25]

The secondary four types of behavior

from which we refrain

[67]

YAN LAG BZHI NI,

With this, we have reached the secondary four negative deeds involved in the one-day vow. They are presented in the following lines of the root text:

[68]

MAL CHE MTHO,

,CHANG ‘THUNG GAR SOGS PHRENG SOGS DANG,

,PHYI DRO’I KHA ZAS YAN LAG BZHI,

,ZHES GSUNGS TE

(9)

The secondary four are high expensive seats;

Drinking alcohol; dancing and so on,

Ornamentation and such; and food after noon.

[69]

MAL GYI KHRI STAN GNYIS NI RIN THANG CHE BA DANG KHRU GANG LAS LHAG PA’I MTHO BA YAN LAG DANG PO DANG,

There are two kinds of “seats” being referred to here: (1) a bed or chair which is especially expensive; or (2) a bed or chair which is higher than a cubit.[26] The first of the four secondary components then is to refrain from using such pieces of furniture for the day.

[70]

‘BRAS DANG NAS LA SOGS PA’I ‘BRU’I RIGS LAS BYUNG BA’I CHANG DANG RGUN ‘BRUM SOGS ‘BRAS BU’I RIGS LAS BYUNG BA BCOS PA’I CHANG SOGS BAG MED THAMS CAD KYI RTZA BA MYOS ‘GYUR ‘THUNG BA YAN LAG GNYIS PA,

The second component is to refrain from drinking alcohol—that substance that we refer to as “crazy-maker,” and which causes all kinds of mindless behavior. This can refer either to alcohol which is distilled from grains such as rice or barley; or to that which is fermented, using different kinds of fruit, such as grapes—or intoxicants produced from other substances, such as drugs.

[71]

LUS KYI YAN LAG BSKYOD PAS GAR DANG SOGS SGRAS BSDUS PA BLU {%GLU} DANG ROL MO BYA BA DANG, RIN PO CHE SOGS RGYAN GYI PHRENG BA DANG SOGS SGRAS BSDUS PA DRI ZHIM PO’I SPOS LUS LA BYUGS PA DANG KHA DOG MDZES PAS LUS BSGYUR BA SOGS YAN LG {%LAG} GSUM PA DANG,

The third component is to refrain from dancing, where you are moving the limbs of your body, and so on—which includes things like singing or playing music. Another part of this component is to refrain from wearing ornamentation such as jewelry made of precious gems or metals, and such—which includes things like applying fragrances to your body; treating your complexion with rouge; and so on.

[72]

NYIN GUNG YOL BA’I PHYI DRO’I DUS NAS SANG GI SKYA RENGS MA SHAR GYI BAR KHA ZAS BZA’ BA’I YAN LAG STE YAN LAG BZHI‘O,,

Finally there is a component of refraining from eating food after noon—meaning from the time after twelve o’clock has passed, on up to daybreak of the following day. These then are the four secondary types of behavior from which we refrain, during the one-day vow.

[73]

GZHAN YANG RTZANG {%RTZA BA} BZHI SPONG NGA {%BA} NI TSUL KHRIMS KYI YAN LAG DANG, CHANG SPONG BA BAG YOD KYI YAN LAG DANG, YAN LAG GZHAN GSUM SPONG BA BRTUL ZHUGS KYI YAN LAG YIN TE MDZOD LAS,

We can also say that the four root types of behavior refrained from here represent a component of observing an ethical life; giving up alcohol in the vow represents a component of maintaining our awareness; and giving up the other three types of behavior represents a component of spiritual self-denial. As the Treasure House of Higher Knowledge puts it,

[74]

,TSUL KHRIMS YAN LAG BAG YOD PA’I,

,YAN LAG BRTUL ZHUGS YAN LAG TE,

,BZHI GCIG DE BZHIN GSUM RIM BZHIN,

,ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR RO,,

There is a component

Of the ethical life;

A component of

Maintaining awareness;

And a component

Of spiritual self-denial:

Respectively they are four,

And one, and then three.[27]

How the one-day vow is taken

[75]

DE LTA BU’I SDOM PA NOD PA’I KUN SPYOD NI, GNAS DMA’ BAR ‘DUG CING RGYAN CHA SOGS SPANGS TE SLOB DPON GYI RJES SU BZLOS PA’I TSIG LAN GSUM DU BZLOS TE SDOM PA NOD PAR BYA STE, MDZOD LAS,

How is it that we take on this kind of vow? We sit in a place which is lower than that where the person granting us the vow is sitting; and we are careful to refrain from things like wearing ornaments. The vow is taken on then by repeating the wording after our master, who repeats the wording themselves three times through. As the Treasure House again puts it,

[76]

,DMA’ BAR ‘DUG SMRAS BZLAS PA YIS,

,MI BRGYAN NAM NI LANGS {%NANGS} BAR DU,

,BSNYEN GNAS YAN LAG TSANGS PAR NI,

,NANG BAR GZHAN LAS NOD PAR BYA,

,ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR RO,,

It is taken through sitting lower,

And repeating what is said,

Without any ornaments on;

And it’s kept until daylight breaks.

You take it from another

In the morning; the one-day vow,

Complete in all its parts.[28]

The basic nature of the lifetime layperson’s vow

[77]

GNYIS PA DGE BSNYEN GYI SDOM PA LA GNYIS, SDOM PA’I NGO BO BSHAD PA DANG, DBYE BA’O, ,DANG PO NI,

Here secondly we identify the nature of the second type: the lifetime vows of a layperson. We’ll begin with a description of its basic nature, and then go on to its divisions. The first is described in the next lines of the root text:

[78]

,GSOD RKU SMRA DANG LOG PAR GA-YEM,

,MYOS ‘GYUR ‘THUNG BA LNGA SPONG PA,

,DGE BSNYEN GYI NI SDOM PA’O,

(10)

The lifetime layperson’s vow is to give up

The five of killing, stealing, and lying,

Sexual misconduct, and taking intoxicants.

[79]

,ZHES GSUNGS TE YAN LAG DANG PO GANG ZAG GZHAN GSOD BA {%PA} STE SROG GCOD PA DANG, GNYIS PA GZHAN GYI RDZAS RKU BA STE MA BYIN PAR LEN PA DANG, GSUM PA RDZUN SMRA BA DANG,

The first component here is to refrain from killing, meaning to take another person’s life. The second is to refrain from stealing; that is, taking what belongs to another, without their having given it to you. The third is lying.

[80]

BZHI PA GANG ZAG GZHAN GYI CHUNG MA DANG, TSANGS SPYOD LA GNAS PA DANG, SBRUM MA DANG, NAD KYIS NYEN PA DANG, NYIN MO DANG, DKON MCHOG GI RTEN DANG SLOB DPON GYI DRUNG LA SOGS PAR ‘DOD PA SPYOD PA’I LOG PAR G-YEM PA DANG,

The fourth component is misconduct in our sexual behavior: for example, having sex with another person’s wife;[29] with someone who is keeping celibacy; where there would be a risk of contracting a disease; out in the open daylight;[30] in the presence of an altar with its representations of the Three Jewels; or in the close vicinity of our spiritual master.

[81]

LNGA PA MYOS ‘GYUR TE CHANG ‘THUNG BA DANG LNGA SPONG BAS RAB TU PHYE BA DE NI DGE BSNYEN GYI NI SDOM PA’O, ,ZHES SO,,

The fifth component is to give up taking intoxicants: alcohol or the like. What distinguishes the lifetime layperson’s vow, Je Tsongkapa is saying here, is to give up these five components.

The different divisions of the lifetime layperson’s vow

[82]

GNYIS PA DBYE BA LA GNYIS, DBYE BA DNGOS DANG, SO SOR NGOS [f.6b] BZUNG BA’O, ,DANG PO NI,

Now for our second point—the divisions of this type of vow. We’ll cover this in two steps: the actual divisions, and then identifying just what they involve. The first is indicated in the next lines of the root text—

[83]

,SNA GCIG SNA ‘GA’ PHAL CHER SPYOD,

,YONGS RDZOGS SPYOD DANG TSANGS SPYOD DANG,

,SKYABS ‘GRO’I DGE BSNYEN RNAM PA DRUG

(11)

Keeping one of them, a couple, most,

And keeping all; keeping celibacy,

And a refuge layperson: these are the six.

[84]

,CES GSUNGS TE DGE BSNYEN GYI SDOM PA LA DBYE NA SGRAS BRJOD RIGS KYI SGO NAS, SNA GCIG SPYOD PA’I DGE BSNYEN, SNA ‘GA’ SPYOD PA’I DGE BSNYEN, PHAL CHER SPYOD PA’I DGE BSNYEN {%,} YONGS RDZOGS SPYOD PA’I DGE BSNYEN DANG, TSANGS SPYOD DGE BSNYEN DANG, SKYABS ‘GRO TZAM GYI DGE BSNYEN TE RNAM PA DRUG GO ,ZHES SO,,

What this is saying is that the lifetime layperson’s vow may be divided—although only nominally[31]—into six different types: the lifetime layperson’s vow where we agree to keep only one of the commitments; where we agree to keep a couple of them; to keep most of them; to keep all of them; to keep celibacy as a layperson, for the rest of our life; and finally where, again as a layperson, we accept the commitments of taking refuge.

[85]

GNYIS PA SO SOR NGOS BZUNG BA NI,

Here secondly we identify what these involve.

[86]

,RTZA BA BZHI LAS GCIG GNYIS GSUM,

,’DOD LOG MI TSANGS SPYOD SPONG DANG,

,SKYABS ‘GRO TZAM GYI DGE BSNYEN DU,

,KHAS LEN RNAMS DANG GO RIM BZHIN,

(12)

These consist respectively of agreeing

To give up one, two, or three of the root four;

To give up sexual misconduct, and all sexual activity,

And to keep just the lay vow of going for refuge.

[87]

,ZHES GSUNGS TE RTZA BA BZHI LAS LOG G-YEM MA GTOGS PA SROG GCOD LTA BU GANG YANG RUNG BA SNA GCIG SPONG BA DANG, LOG G-YEM MA GTOGS PA SNA GNYIS SPONG BA DANG, DE MA GTOGS PA SNA GSUM SPONG BA DANG,

What this is saying is that these different types consist of agreeing to give up—respectively—the following. For the first, we commit to giving up any one of the root four types of negative behavior, with the exception of sexual misconduct: it could be killing, for example. For the second, we give up any two of these four, again with the exception of sexual misconduct. For the third, we give up three types of behavior, with the same exception.

[88]

SNA GSUM GYI STENG DU ‘DOD PAS LOG PAR G-YEM PA SPONG BA DANG, SNA GSUM GYI STENG DU MI TSANGS SPYOD SPONG BA DANG, SPANG BYA LNGA PO GANG YANG MI SPONGS BAR SKYABS SU ‘GRO BA TZAM GYI SGO NAS DGE BSNYEN DU KHAS LEN PA STE DRUG PO DE RNAMS DANG SNGAR GYI DBYE BA DRUG PO GO RIM BZHIN DU SBYAR NAS BZUNG BAR BYA’O,

,ZHES SO,,

When we agree to give up sexual misconduct, on top of the other three, this is the fourth type mentioned; when on top of the three we commit to give up all sexual activity, this is the fifth. And then the sixth is where—even if we don’t agree to give up any of the five undesirable actions already listed—we commit just to keeping the lay vow of going for refuge. And so the two lists match up consecutively, with six items each.

Vows of a novice monk or nun

[89]

GSUM PA DGE TSUL GYI SDOM PA NI,

Here then is the nature of the third type of vow: that for novice monks or nuns. It is presented in the following lines of the root text:

[90]

,RTZA BA BZHI DANG YAN LAG DRUG

,BCU SPONG DGE TSUL SDOM PA’O,

(13)

The novice vow is giving up ten:

The root four and the secondary six.

[91]

,ZHES GSUNGS TE SNGAR BSHAD PA’I RTZA BA BZHI DANG YAN LAG DRUG STE SPANG BYA BCU SPONG BAS RAB TU PHYE BA’I SDOM PA DGE TSUL GYI SDOM PA’O,,

The novice vow then is characterized by giving up ten different kinds of negative behavior: the root four that we covered already above; and then six secondary components.

How we arrive at six secondary components for the novice vow

[92]

YAN LAG DRUG STON PA’I PHYIR

And the next lines of the root text are meant to cover the six secondary components of this vow:

[93]

,GAR SOGS PHRENG BA [f.7a] SOGS RNAM PA {%RNAM} GNYIS DANG,

,GSER DNGUL LEN DANG RNAM {%PA} GSUM,

,PHYE BAS YAN LAG DRUG DU ‘GYUR,

(14)

The secondary come to six, by dividing into two

Dancing and so on, and ornamentation and such;

And then adding handling money to make three.

[94]

,ZHES GSUNGS TE BSNYEN GNAS KYI SKABS KYI YAN LAG BZHI PA’I YAN LAG GSUM PA DE LA GAR SOGS KYI YAN LAG DANG, PHRENG SOGS KYI YAN LAG RNAM PA GNYIS DANG, GSER DNGUL LEN PA’I YAN LAG DANG RNAM PA GSUM DU PHYE BA DE, MAL STAN CHE MTHO DANG CHANG DANG PHYI DRO’I KHA ZAS BCAS GSUM GYI STENG DU BSNAN PAS YAN LAG DRUG TU ‘GYUR RO, ,ZHES SO,,

Here then, says Je Tsongkapa, is how we come to six different secondary components here. First we take the two parts of the third of the four secondary components of the one-day vow, and divide them out: (1) “dancing and so on”; and (2) “ornamentation and such.” Then we add (3) handling money, to make three. On top of these we add the three of (4) high, expensive seats; (5) drinking alcohol [which as noted above includes using any other type of intoxicant]; and (6) taking food after noon.

How we arrive at thirteen commitments for a novice

[95]

SPANG BYA BCU GSUM DU ‘GYUR TSUL BSTAN PA’I PHYIR,

How we then arrive at the thirteen commitments of a novice is presented in the next part of the root text:

[96]

,MKHAN POR GSOL BA GDAB PA DANG,

,KHYIM PA’I RTAGS NI SPANGS PA DANG,

,RAB BYUNG RTAGS NI LEN PA LAS,

,NYAMS PA RNAM GSUM BSNAN PA YIS,

,SPANG BYA BCU GSUM DAG TU ‘GYUR,

,ZHES GSUNGS TE,

(15)

To arrive at the thirteen things to give up,

To these then add the three failures:

Not making supplications to your preceptor,

Giving up the appearance of a layperson,

And taking on the appearance of the ordained.

[97]

RTZA BA BZHI DANG YAN LAG DRUG GI STENG DU MKHAN POR GSOL BA GDAB PA LAS NYAMS PA DANG, KHYIM PA’I RTAGS NI SPANGS PA LAS NYAMS PA DANG NI RAB TU BYUNG BA’I RTAGS NI LEN PA LAS NYAMS PA STE, NYAMS PA RNAM GSUM BSNAN PA YIS NI SKABS ‘DI’I SPANG BYA BCU GSUM DAG TU ‘GYUR RO ZHES SO,,

What these lines are saying is that we take the root four, and the secondary six, and add to them what we call the “three failures”—to make a total of thirteen things to be given up. The three failures are (1) failing to make supplication to the one who gives us our vows; (2) failing to renounce the attire and so on that mark us as a householder; (3) failing to assume the attire and so on that mark us as someone who is ordained.

[98]

GSER DNGUL LEN PA MTSON PA TZAM STE RIN PO CHE’I RIGS GANG YANG RUNG, DE DANG DE LA NGO BO’I SGOS {%SGO NAS?} MI RUNG BA’I BLO MA BZHAG PAR NOR GYI ‘DU SHES BZHAG STE BDAG GIR BYED PA’O,,

When we talk here about “handling money”—literally “handling gold and silver”—we are only mentioning a representative example; this can apply just as well to handling any precious gem, metal, or similar monetary instrument. The point is that we fail to think of whatever it may be as being, in its basic nature, inappropriate; we conceive of it as wealth, and then we act to make it our own.

[99]

NYAMS PA RNAM GSUM LAS MKHAN POR GSOL BA GDAB PA LAS NYAMS PA NI, MKHAN PO LA MA GUS PA NYID DANG, CHOS LDAN GYI BKA’ SGRUB NUS BZHIN DU MI SGRUB PA SOGS YIN LA,

What exactly does it mean, in the description of the three failures, to “fail to make supplication to the one who gives us our vows”? This is nothing other than failing to respect the one who has given us our vows, and similar things—such as failing to carry out their instructions, when these instructions are spiritually appropriate and we do have the capacity to fulfil them.

[100]

KHYIM PA’I RTAGS SPANGS PA LAS [f. 7b] NYAMS PA NI, KHA TSAR DANG PHUN TSAR MA BCAD PA’I SKA RAGS DANG, GOS DKAR PO SOGS KHYIM PA’I RTAGS BGOS SHING ‘CHANG BA SOGS YIN,

And what is it to “fail to renounce what would mark us as a householder”? This refers to where for example we wear a monk’s belt which has fancy fringes or tassles; or we wear or keep clothing which is white—all of which would mark us as a householder.

[101]

RAB BYUNG GI RTOGS {%RTAGS} BLANGS PA LAS NYAMS PA NI, BLA GOS DANG THANG GOS SOGS MED PA DANG, MU STEGS CAN GYI RTAGS DANG CHA LUGS ‘CHANG BA SOGS YIN NO,,

And what is it to “fail to assume the attire and so on that mark us as someone who is ordained”? This is where we fail to wear the upper and lower parts of the robes of a Buddhist who is ordained; or else keep or wear the clothes and other accoutrement of someone outside of the tradition—and so on.

[102]

DGE TSUL DU SGRUB PA’I SLOB DPON NI KHA SKONG GI CHOS BCU GSUM DANG, BRTAN MKHAS KYI YON TAN GNYIS DANG LDAN PA ZHIG DGOS PAR GSAL ZHING, DE DAG JI LTAR YIN PA NI DGE SLONG GI SKABS SU ‘CHAD DO,,

It is completely clear that the vowmaster who makes of us a novice should possess the thirteen “completing” qualities, as well as the two qualities of being stable and wise. How these qualities are described is something we will cover when we reach the section on full nuns and monks.

The ceremony for ordaining a novice

[103]

‘DI LA YANG THOG MAR RAB TU BYUNG DGOS LA, DE YANG SDOM PA SKYE BA DANG GNAS PA DANG MDZES PA DANG KHYAD PAR DU ‘GYUR BA’I BAR CHAD DU MI ‘GYUR BA ZHIG DGOS PAS,

Now this person must be someone who started out with leaving the home life; and they must be someone who has not encountered a serious obstacle to the formation of their vows; or to the continuation of these vows; or to their beautification; or to their eminence.

[104]

BSGRUB BYA DE LA MKHAN POS BAR CHAD ‘DRI BA DANG ‘KHOR BA’I NYES DMIGS DANG THAR PA’I PHAN YON LEGS PAR BRDA’ SPRAD PA’I SGO NAS, NGES ‘BYUNG GI BSAM PA SKYED DU ‘JUG PA DANG MKHAN POR GSOL BA GDAB PA DANG,

The vowmaster must inquire of the candidate as to any potential obstacles they may possess; and they should as well acquaint them thoroughly with the problems of the cycle of pain, and the benefits of attaining freedom. In this manner the master inspires thoughts of renunciation within the candidate; and this then is followed with the supplication where the candidate requests the master for their vows.

[105]

GTZUG PHUD BREGS TE KHRUS BYED PA DANG,

After that, the master wets the lock of the candidate’s remaining hair and then cuts it.[32]

[106]

MKHAN PO’I ZHABS LA GTUGS TE PHYAG ‘TSAL TU ‘JUG PA DANG,

The candidate is then instructed to “touch the vowmaster’s feet”—meaning to prostrate to the vowmaster.

[107]

BLA GOS THANG GOS GDING BA LHUNG BZED CHU TSAG DANG BCAS PA’I YO BYAD RNAMS GTAD PA DANG,

Next, the vowmaster conveys to the candidate their monastic accoutrement: upper robe, lower robe, ceremonial seat, sages’s bowl, and water strainer.

[108]

SKYABS SU ‘GRO BA SNGON DU ‘GRO BAS RAB BYUNG GI TSUL KHRIMS NOD PA DANG,

And then the vowmaster grants the candidate the commitments of an ordained person, after first taking them through going for shelter.

[109]

NYAMS PA RNAM GSUM SPONG BAR KHAS LEN PA DANG,

The master then leads the candidate through the commitment to always avoid the three failures.

[110]

BSAM PA DANG RTAGS DANG MING BRDZE {%BRJE} BA STE BRJE BA GSUM GYI DON LA BRDA’ LEGS PAR SPROD PA SOGS RAB BYUNG GI CHOG {%CHO GA} ‘DUL BA’I MDO DANG DGONGS ‘GREL TSAD LDAN DAG LAS GSUNGS PA LTAR MA NOR BAR BYA LA,

And then they acquaint the candidate very carefully with what are called the “three changes”: the change in the way they think; in their appearance; and in the name they are called. All these details of the ceremony for leaving the home life should be followed without any error—in exact accordance with the instructions given in the Sutra on Vowed Morality, and in authoritative commentaries upon it.

[111]

DGE TSUL MA’I SDOM PA LEN PA’I TSUL, BSGYUR PHRAN BU RE MA GTOGS CHOG {%CHO GA} DANG KUN SPYOD DGE TSUL [f. 8a] JI LTA BA BZHIN DU BYA’O,,

As for how a candidate takes the vows of a novice nun, the ceremony and activities should be done in the same way as they are for the novice monk—with just a few minor adjustments.

To be continued!!!

Je Tsongkapa’s Root Text:

The Essence of the Ocean

of Vowed Morality

SO SOR THAR BA’I SDOM PA GTAN LA DBAB PA, ‘DUL BA RGYA

MTSO’I SNYING PO BSDUS PA ZHES BYA BA,

The Essence of the Ocean of Vowed Morality:

A Presentation on the Vows of Individual Freedom

Please note that—since Je Tsongkapa’s text quickly breaks out of standard 4-line Tibetan verses, we have numbered the sections according to the topical divisions of our commentator, Gyal Kenpo, Drakpa Gyeltsen.

AOm BDE LEGS SU GYUR CIG

Om! May there be happiness and goodness.

THAMS CAD MKHYEN PA LA PHYAG ‘TSAL LO

I bow down to the Omniscient One.

,GANG LA BRTEN NAS BDE BLAG TU,

,THAR PA’I GRONG DU BGROD PA’I THABS,

,BDE GSHEGS BSTAN PA’I SNYING PO MCHOG

,SO SOR THAR CES GRAGS PA GANG,

(1)

There is something which, if you rely on it,

Is the way to travel with ease to the city of freedom;

The supreme essence of the teachings of those Gone to Bliss;

It is that which is known as “individual freedom.”

,NGO BO DANG NI RAB DBYE DANG,

,SO SO’I NGOS ‘DZIN SKYE BA’I RTEN,

,GTONG [f. 3b] BA’I CHA {%RGYU} DANG PHAN YON TE,

,RNAM PA DRUG GIS JI BZHIN BSHAD,

(2)

In keeping, I shall explain them in six categories:

Their basic nature, the way they are divided,

Their individual descriptions, who can take them,

How they are lost,[33] and the benefits they give.

,NGES ‘BYUNG BSAM BAS {%PAS} RGYU BYAS NAS,

,GZHAN GNOD GZHI DANG BCAS PA LAS,

,LDOG PA

(3)

It is a turning away from harming others,

And its basis, caused by an attitude

Of renunciation.

,DE YANG LUS GA {%NGAG} LAS,

,GZUGS CAN YIN ZHES ‘DOD PA DANG,

,SPONG BA’I SEMS PA RGYUN CHAGS PA,

,SA BON DANG BCAS YIN NO ZHES,

,’DOD PA’I TSUL NI RNAM PA GNYIS,

,RANG GI SDE PA GONG ‘OG SMRA,

(4)

It is physical and verbal karma

Which they assert is physical matter.

The others say it is the intention to give up

And its seed as it continues in your mind.

Thus our schools’ positions are two:

What the higher and lower assert.

,BSNYEN GNAS DGE BSNYEN PHA MA DANG,

,DGE TSUL PHA MA DGE SLOB MA,

,DGE SLONG MA DANG DGE SLONG [f. 4b] STE,

,SO SOR THAR PA RIGS BRGYAD DO,

(5)

There are eight different classes

For the vows of individual freedom:

The one-day vow; male and female layperson vows;

Male and female novice vows;

Intermediate nun’s vows; and the vows

Of a fully ordained nun or monk.

,KHYIM PA’I SDOM PA DANG PO GSUM,

,RAB BYUNG SDOM PA THA MA LNGA,

(6)

The first three vows are for laypeople,

The last five vows for the ordained.

,RTZA BA BZHI DANG YAN LAG BZHI,

,BRGYAD SPONG BSNYEN GNAS SDOM PA’O,

(7)

The one-day vow is to give up eight:

The root four and the secondary four.

,MI TSANGS SPYOD DANG MA BYIN LEN,

,SROG GCOD RDZUN TU SMRA BA RNAMS,

,RTZA BA BZHI YIN,

(8)

The root four are sexual activity,

Stealing, killing, and speaking lies.

MAL CHE MTHO,

,CHANG ‘THUNG GAR SOGS PHRENG SOGS DANG,

,PHYI DRO’I KHA ZAS YAN LAG BZHI,

(9)

The secondary four are high expensive seats;

Drinking alcohol; dancing and so on,

Ornamentation and such; and food after noon.

,GSOD RKU SMRA DANG LOG PAR GA-YEM,

,MYOS ‘GYUR ‘THUNG BA LNGA SPONG PA,

,DGE BSNYEN GYI NI SDOM PA’O,

(10)

The lifetime layperson’s vow is to give up

The five of killing, stealing, and lying,

Sexual misconduct, and taking intoxicants.

,SNA GCIG SNA ‘GA’ PHAL CHER SPYOD,

,YONGS RDZOGS SPYOD DANG TSANGS SPYOD DANG,

,SKYABS ‘GRO’I DGE BSNYEN RNAM PA DRUG

(11)

Keeping one of them, a couple, most,

And keeping all; keeping celibacy,

And a refuge layperson: these are the six.

,RTZA BA BZHI LAS GCIG GNYIS GSUM,

,’DOD LOG MI TSANGS SPYOD SPONG DANG,

,SKYABS ‘GRO TZAM GYI DGE BSNYEN DU,

,KHAS LEN RNAMS DANG GO RIM BZHIN,

(12)

These consist respectively of agreeing

To give up one, two, or three of the root four;

To give up sexual misconduct, and all sexual activity,

And to keep just the lay vow of going for refuge.

,RTZA BA BZHI DANG YAN LAG DRUG

,BCU SPONG DGE TSUL SDOM PA’O,

(13)

The novice vow is giving up ten:

The root four and the secondary six.

,GAR SOGS PHRENG BA [f.7a] SOGS RNAM PA {%RNAM} GNYIS DANG,

,GSER DNGUL LEN DANG RNAM {%PA} GSUM,

,PHYE BAS YAN LAG DRUG DU ‘GYUR,

(14)

The secondary come to six, by dividing into two

Dancing and so on, and ornamentation and such;

And then adding handling money to make three.

,MKHAN POR GSOL BA GDAB PA DANG,

,KHYIM PA’I RTAGS NI SPANGS PA DANG,

,RAB BYUNG RTAGS NI LEN PA LAS,

,NYAMS PA RNAM GSUM BSNAN PA YIS,

,SPANG BYA BCU GSUM DAG TU ‘GYUR,

(15)

To arrive at the thirteen things to give up,

To these then add the three failures:

Not making supplications to your preceptor,

Giving up the appearance of a layperson,

And taking on the appearance of the ordained.

To be continued!

Appendices

Comparative list of the names

of divine beings & places

English Sanskrit Chinese Tibetan

Victor Jina 最勝 rGyal-ba

Bibliography of w

orks

originally written in Sanskrit

S1

Śākyamuni Buddha (Tib: Sh’akya thub-pa), 500bc. The Tip of Diamond: A Secret Teaching of the Great Practice of What is Secret (Vajra Śekhara Mahāguhya Yoga Tantra) (Tib: gSang-ba rnal-‘byor chen-po’i rgyud rDo-rje rtze-mo, Tibetan translation at KL00480, ff. 320a-520a of Vol. 6 [Cha] in the “Secret Teachings” Section [Tantra, rGyud] of the bKa’-‘gyur [Lha-sa edition]).

S2

Guṇaprabha (Tib: Yon-tan ‘od), 650bc. A Sutra on Vowed Morality (Vinaya Sūtra) (Tib: ‘Dul-ba’i mdo, Tibetan translation at TD04117, ff. 1b-100a of Vol. 83 (Wu) in the Discipline Section [Vinaya, ‘Dul-ba] of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

S3

Vasubandhu (Tib: dByig-gnyen), c. 350ad. The Treasure House of Higher Knowledge, Set in Verse (Abhidharmakoṣakārikā) (Tib: Chos mngon-pa’i mdzod kyi tsig-le’ur byas-pa, Tibetan translation at TD04089, ff. 1b-25a of Vol. 2 [Ku] in the Higher Knowledge Section [Abhidharma, mNgon-pa] of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

Bibliography of works

originally written in Tibetan

B1

rGyal mkhan-po (Grags-pa rgyal-mtsan) (1762- 1836). The String of Precious Jewels: A Brief Word-by-Word Commentary on the “Essence of the Ocean of Vowed Morality” (‘Dul-ba rgya-mtso’i snying-po bsdus-pa’i tsig-‘grel Rin-chen phreng-ba, ACIP digital text @), 50ff.

B2

rJe Tsong-kha-pa (Blo-bzang grags-pa) (1357-1419). The Brief Essence of the Ocean of Vowed Morality: A Work Outlining the Vows of Individual Freedom (So-sor thar-pa’i sdom-pa gtan la dbab-pa ‘Dul-ba rgya-mtso’i snying-po bsdus-pa, ACIP S05275-63), 2ff.

B3

Si-khron Mi-rigs dpe-skrun khang. The “Treasure” Catalog of Tibetan Collected Works, Vol. 1 (Shes-bya’i gter-mdzod, deb dang-po, ACIP R00003), 520pp.

B4

rJe Tsong-kha-pa (Blo-bzang grags-pa) (1357-1419). The Cow that Produces Every Wish: An Extensive Explanation of the Practice of Realization for the Secret Teaching of the Conqueror, the Glorious Sphere of Highest Bliss (Chakrashanvara), ACIP S05320), 184ff.

B5

sKyabs-rje Khri-byang rin-po-che (Blo-bzang ye-shes bstan-‘dzin rgya-mtso) (1901-1981). A Compilation of Various Teachings Delivered on the Subject of Developing the Good Heart, and Similar Topics (Blo-sbyong gi skor sogs gsung thor-bu’i rigs rnams phyogs gcig tu bsdebs-pa, ACIP S12412), 71ff.

B6

(Paṇ-chen bla-ma sku-phreng dang-po) Blo-bzang chos kyi rgyal-mtsan (1570-1662), “The Explication of the First Chapter,” Part of “The Ocean of Fine Explanation, which Clarifies the Essence of the Essence of the ‘Jewel of Realizations,’ a Classical Commentary of Advices on the Perfection of Wisdom” (Shes-rab kyi pha-rol tu phyin-pa’i man-ngag gi bstan-bcos mNgon-par rtogs-pa’i rgyan gyi snying-po’i snying-po gsal-bar Legs-par bshad-pa’i rgya-mtso las sKabs dang-po’i rnam-par bshad-pa, ACIP S05942), 41ff.

B7

Pha-bong kha-pa Rin-po-che (bDe-chen snying-po) (1878-1941). “A Gift of Liberation, Thrust into the Palm of Your Hand; the Heart of the Nectar of Holy Advices; the Very Essence of All the Highest of Spoken Words,” representing Profound, Complete, and Unerring Instruction taken down as Notes during a Teaching, of the Kind Based on Personal Experience, on the Steps of the Path to Enlightenment, the Heart-Essence of the Incomparable King of the Dharma (rNam-grol lag-bcangs su gtod-pa’i man-ngag zab-mo tsang la ma-nor-ba mtsungs-med chos kyi rgyal-po’i thugs-bcud byang-chub lam gyi rim-pa’i nyams-khrid kyi zin-bris gsung-rab kun gyi bcud-bsdus gdams-ngag bdud-rtzi’i snying-po Lam-rim rnam-grol lag-bcangs, ACIP S00004), 392ff.

B8

‘Jam-dbyangs bzhad-pa Ngag-dbang brtzon-‘grus (1648-1721). The End of All Error, a Lovely String of Wishing Jewels, Necklace for Those of Clear Intellect, and Fulfillment of the Hopes of Those with Goodness: A Critical Examination of Difficult Points in the Teachings on Buddhist Discipline (‘Dul-ba’i dka’-gnas rnam-par dpyad-pa ‘Khrul-spong blo-gsal mgul-rgyan tzinta ma-ṇi’i phreng-mdzes sKal-bzang re-ba kun-skong, ACIP S00839) in two volumes of 316ff and 158ff.

B9

(rGyal-ba) dGe-‘dun grub (1391-1474). Illumination of the Path to Freedom: An Explanation of the Holy “Treasure House of Higher Knowledge” (Dam-pa’i Chos-mngon-pa mdzod kyi rnam-par bshad-pa Thar-lam gsal-byed, ACIP SE05525), 205ff.

B10

lCang-skya Rol-pa’i rdo-rje (1717-1786). Part Two of “The Lovely Jewel for the Mountain Peak of the Teachings of the Able Ones”: A Survey which Clearly Explains the Schools of Philosophy (Grub-pa’i mtha’i rnam-par bzhag-pa gsal-bar bshad-pa Thub-bstan lhun-po’i mdzes-rgyan zhes-bya-ba las sde-tsan gnyis-pa, ACIP S00061), 36ff.

B11

dNgul-chu Dharma Bhadra (1772-1851). The Maker of Day, which Illumines the True Thought of Lobsang: A Commentary on ‘The Essence of the Ocean of Vowed Morality’ (‘Dul-ba rgya-mtso’i snying-po’i ṭ‘ika Blo-bzang dgongs-don gsal-ba’i nyin-byed, ACIP S06361), 13ff.

B12

(Co-ne Bla-ma) Grags-pa bshad-sgrub (1675-1748). The Sun Which Illuminates the True Thought of the Throng of the Realized, All the Able Ones and their Children: A Commentary upon the “Treasure House of Higher Knowledge” (Chos-mngon mdzod kyi t’ikka rGyal-ba sras bcas ‘phags-tsogs thams-cad kyi dgongs-don gsal-bar byed-pa’i nyi-ma, ACIP S00027), 211ff.

B13

Paṇ-chen Blo-gros legs-bzang (fl. 1550). A Jewel to Embellish the True Thought of the String of Jewels in the Great Commentary, an Overview of that Classic, the Root Summary of Vowed Morality (bsTan-bcos ‘Dul-ba mdo rtza-ba’i spyi-don T’ik-chen rin-chen phreng-ba’i dgongs-rgyan, ACIP S00059), in two volumes: Vol. 1, 217ff; Vol. 2, 128ff.

[1] Their knowledge, and their love: The whole verse is a comparison of the Buddhas—here called “Lords of Victors—to the entire physical world according to traditional Buddhist cosmology: a great disk with a massive central mountain, itself lined with wide terraces inhabited by different peoples; a great ocean around the mountain, filled with jewels; and the sun and moon circling the mountain and crossing over four continents below each day. The physical body of an Enlightened Being is adorned with 112 unique signs and marks; and their “reality body” consists of their omniscience, along with their ultimate nature.

[2] All the way to the surrounding mountains: That is, throughout the entire world; in the ancient Buddhist vision of the world, a chain of mountains stands at the very edge of the disk of the world, keeping the waters of the ocean from pouring off.

[3] The all-knowing Shepay Dorje: Referring to Jamyang Shepay Dorje (1648-1721), a highly accomplished lama whose second incarnation, Konchok Jigme (1728-1791), recognized the author of our commentary as the reincarnation of a high master when he was 16 years old, and ordained him as a full monk at 21. See pp. 320-321 of The “Treasure” Catalog of the Collected Works of Tibetan Writers (%B3, ACIP digital text R00003).

[4] All three realms of the universe: Buddhist tradition divides the universe into three sectors: the desire realm; the form realm; and the formless realm. We humans live in the desire realm, a place marked by our fascination with food and sex. The form realm is inhabited by beautiful, powerful beings very similar to the superheroes in modern movies. In the formless realm, people live in almost completely mental bodies. People born into the latter two realms enjoy almost continuous happiness until they die; upon which—because they have squandered all their good karmic seeds—they inevitably drop to the hell realms.

[5] Happiness and goodness: We will be presenting Je Tsongkapa’s root text in bold print throughout; where this is woven into Gyal Kenpo’s commentary, it will again be indicated in bold in the Tibetan, and in italics in the English. In this “weaving” style of commentary, the flow of the native prose sometimes suffers slightly; and the reader will be able to detect this in the corresponding translation as well.

[6] Making a pledge: In commenting, elsewhere, upon this traditional explanation of the sacred syllable of om, Je Tsongkapa himself says that the meaning of “making a pledge” here is that of “leading off mantras”—referring to the frequent function of om as the opening syllable of a mantra. See f. 39a of his famed Cow that Grants Every Wish (%B4, S05320).

[7] The One Who Holds the Jewel: In his explanation of this verse, the illustrious Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche says that the sacred syllable om itself is the “one who holds the jewel,” in the sense of granting us precious goals. He then ties this “jewel” into the one found in the famous mantra, Om mani padme hung. See f. 66b of his collection of teachings on developing the good heart (%B5, S12412).

The entire verse here by the way is drawn from the tantra known as The Tip of Diamond (Vajra Shekhara) (see f. 341b, %S1, KL00480). In the version available to us, there is an additional line between the second and third Tibetan lines here. It says “And to what gives you the fortune of good” (skal-bzang rnam-pa dang ldan zhing).

[10] How all things are: A reference to the unique ability of an Enlightened Being to see directly not only all events in all times; but at the same time also their ultimate nature, or emptiness.

[11] The decree made in times of old: The decree is described as follows by His Holiness the First Panchen Lama, Lobsang Chukyi Gyeltsen (1570-1662): “The kings, royal ministers, and sages of old decreed that at the beginning of a work belonging to the section on vowed morality, the translator should bow down to omniscience; and at the beginning of a work belonging to the section on higher knowledge, to glorious Gentle Voice; and at the beginning of a work belonging to the section on the classics, to the Buddhas and bodhisattvas.” See f. 9a of his “Explication of the First Chapter,” Part of “The Ocean of Fine Explanation, which Clarifies the Essence of the Essence of the ‘Ornament of Realizations,’ a Classical Commentary of Advices on the Perfection of Wisdom,” entry %B6, ACIP S05942).

[12] Those Who Have Gone to Bliss: That is, the Buddhas; the Sanskrit here is Sugata, and the Tibetan Dewar Shekpa. Please note that Gyal Kenpo is purposely weaving Je Tsongkapa’s root text into his commentary, and we will be indicating those words in italics.

[13] Vows of individual freedom: The foundation of all Buddhist ethics; in Sanskrit, called pratimoksha vows; in Tibetan, sosor tarpa. The word moksha (tarpa) means freedom, in the sense of both nirvana (the permanent ending of our negative emotions) and Buddhahood (a state of omniscience and a body that can help all living beings in the universe). Prati (sosor) means individual, and is explained as meaning that the results of taking the vows are an individual matter: those who keep the vows they took will reach freedom; and those who do not will not. See for example ff. 23a-23b of the first part of Jamyang Shepay Dorje’s masterful presentation of vowed morality (%B8, S00839).

[14] Three collections and three trainings: The physical teachings of the Enlightened Beings are divided into three collections: those of vowed morality; sutra; and higher knowledge. These three present, respectively, the traditional three “extraordinary trainings” of an ethical life; meditative concentration; and an understanding of how reality works. See for example f. 51a of Pabongka Rinpoche’s classic presentation of the steps to enlightenment, A Gift of Liberation Thrust into the Palms of Your Hands (%B7, ACIP S00004).

[15] How they are lost: In the carving of Gyal Kenpo’s work available to us, the phrase here—how they are lost—is twice rendered in Tibetan with gtong-ba’i cha, whereas all the other versions in the ACIP database to date (8 of them) have gtong-ba’i rgyu. The latter is also how the poem is recited even today at the twice-monthly ceremony of confession at the major monasteries of Tsongkapa’s lineage. In any case, the meaning of both readings is the same.

[16] Lobsang Drakpa: Ordination name of Je Tsongkapa, author of our root text.

[17] Sutra on Vowed Morality: The great source book for all the Tibetan lineages of vowed morality, composed by the Indian master Guna Prabha around 650ad. Incidentally, the word sutra in the title here is meant in its connotation as “a short book,” and not as “a teaching of the Buddha.” It may be found in the ACIP online library at TD04117 (bibliography entry %S2).

[18] Sutrist and Detailist Schools: Two of the four classical schools of ancient Indian Buddhism; both belonging to the lower way. The teachings on vowed morality are primarily associated with the latter, which is the lowest of these four high schools. “Sutrists” are so called because they consider only the original sutras, or teachings of the Buddha, to constitute ultimate authority. “Detailists” take their name from The Great Explanation of Detail, a classical commentary which they favor. For a discussion of the two names, see respectively f. 9a of the great commentary to The Treasure House of Higher Knowledge (Abhidharma Kosha) by Gyalwa Gendun Drup (1391-1474) (%B9, S05525); and f. 5b of the second part of the masterful survey of Buddhist schools by Changkya Rolpay Dorje (1717-1786) (%B10, S00061).

[19] Attitude of renunciation: At this point, Je Tsongkapa’s root text begins to fall out of regular 4-line verses in the Tibetan. We have therefore numbered the sections of his original work not by an artificial division into these four, but rather by topic, following our commentator.

[20] Higher and lower schools: We have just mentioned the lower schools. The “higher” ones are the Mind-Only School and the Middle-Way School, with its division into two famous branches: the Independent branch and the Consequence branch. These four schools of ancient India should not be confused with the four spiritual traditions of Tibet.

[21] And its basis: The different sets of freedom vows lay primary emphasis on actions of body and speech. The traditional Buddhist list of the “top ten” actions to be avoided gives three actions of body; four of speech; and a final three committed in thought. The “basis” mentioned in Je Tsongkapa’s verse has sometimes been interpreted as referring to these last three, as they provide the inner, mental foundation for outside action. See for example f. 3b of the commentary by Quicksilver Lama, Ngulchu Dharma Bhadra (1772-1851) (%B11, S06361).

[22] Communicating form and non-communicating form: The idea of “communicating form” is unique to the followers of higher knowledge (abhidharma). An example would be the color and shape of our hands when we fold them in the unique manner for taking on a Buddhist vow; this special gesture is form which “communicates” to someone watching us take the vow that we very likely have some kind of extraordinary motivation in our heart at the moment.

Later on, according to this school, there is a sort of an invisible aura around our body, imparted by the holiness of the vow. This is still considered physical, but cannot be seen by a normal person and therefore cannot communicate to them the probable state of our mind. See for example the commentary to the Treasure House of Higher Knowledge by Choney Lama Drakpa Shedrup (1675-1748), itself a translation in the current Diamond Cutter Classics Series. The reference may be found on f. 103b (%B12, S00027).

[23] Higher and lower schools: Here simply referring to the higher and lower of the lower two of the four schools of ancient India.

[24] Insert our jewel: The “jewel” is a reference to the male penis; it is emphasized here since at the time this commentary was primarily intended for monks. In modern times we can consider the equivalent action for a female as well. The three “open wounds” is a traditional scriptural expression meant to refer to the mouth; the female vagina; and the anus. See f. 147b of the first volume of the extraordinary commentary to vowed morality by Panchen Lodru Leksang (%B13, SL00059). His exact dates are unknown, but we can say that he was active around 1550, since he is said to have served as the 9th throneholder of Tashi Hlunpo Monastery; and we know that the 7th throneholder, Lodru Gyeltsen, lived 1487-1567.

[25] Still actions that wise people refrain from: That is, the one-day vow here technically involves only giving up the classic, worst-possible versions of these misdeeds. But our author is encouraging us to go further and give up as well even lesser forms of them.

[26] Higher than a cubit: That is, higher than the length from ones elbow to the tip of ones middle finger.

[27] And then three: See f. 12a of Master Vasubandhu’s classic (%S3, TD04089).

[28] Complete in all its parts: See ff. 11b-12a of the same work.

[29] Another person’s wife: Again, the primary audience for our author’s work during his time was males; but of course the vow applies to sex with another person’s husband as well.

[30] In the open daylight: Meaning, in any open space where we could possibly be observed by others.

[31] Although only nominally: This is a technical term in Buddhist scripture for indicating that the divisions offered are somehow not technically precise or entirely accepted. Lamas giving these vows in the present day will point out that committing to less than all four of the components listed is not really taking lifetime layperson’s vows.

[32] Cuts a lock: In olden times, the candidate’s entire head would be shaved at this point. In recent centuries, perhaps due to the fact that many candidates may be ordained at the same time, the head is shaved prior to the ordination ceremony but a small tuft is left—and this is cut off during the ceremony.

[33] How they are lost: Here we repeat a note from above, in the commentary. In the carving of Gyal Kenpo’s work available to us, the phrase here—how they are lost—is twice rendered in Tibetan with gtong-ba’i cha, whereas all the other versions in the ACIP database to date (8 of them) have gtong-ba’i rgyu. The latter is also how the poem is recited even today at the twice-monthly ceremony of confession at the major monasteries of Tsongkapa’s lineage. In any case, the meaning of both readings is the same.

Comments

Comments are closed

0 Comments on the whole Page

0 Comments on block 1

0 Comments on block 2

0 Comments on block 3

0 Comments on block 4

0 Comments on block 5

0 Comments on block 6

0 Comments on block 7

0 Comments on block 8

0 Comments on block 9

0 Comments on block 10

0 Comments on block 11

0 Comments on block 12

0 Comments on block 13

0 Comments on block 14

0 Comments on block 15

0 Comments on block 16

0 Comments on block 17

0 Comments on block 18

0 Comments on block 19

0 Comments on block 20

0 Comments on block 21

0 Comments on block 22

0 Comments on block 23

0 Comments on block 24

0 Comments on block 25

0 Comments on block 26

0 Comments on block 27

0 Comments on block 28

0 Comments on block 29

0 Comments on block 30

0 Comments on block 31

0 Comments on block 32

0 Comments on block 33

0 Comments on block 34

0 Comments on block 35

0 Comments on block 36

0 Comments on block 37

0 Comments on block 38

0 Comments on block 39

0 Comments on block 40

0 Comments on block 41

0 Comments on block 42

0 Comments on block 43

0 Comments on block 44

0 Comments on block 45

0 Comments on block 46

0 Comments on block 47

0 Comments on block 48

0 Comments on block 49

0 Comments on block 50

0 Comments on block 51

0 Comments on block 52

0 Comments on block 53

0 Comments on block 54

0 Comments on block 55

0 Comments on block 56

0 Comments on block 57

0 Comments on block 58

0 Comments on block 59

0 Comments on block 60

0 Comments on block 61

0 Comments on block 62

0 Comments on block 63

0 Comments on block 64

0 Comments on block 65

0 Comments on block 66

0 Comments on block 67

0 Comments on block 68

0 Comments on block 69

0 Comments on block 70

0 Comments on block 71

0 Comments on block 72

0 Comments on block 73

0 Comments on block 74

0 Comments on block 75

0 Comments on block 76

0 Comments on block 77

0 Comments on block 78

0 Comments on block 79

0 Comments on block 80

0 Comments on block 81

0 Comments on block 82

0 Comments on block 83

0 Comments on block 84

0 Comments on block 85

0 Comments on block 86

0 Comments on block 87

0 Comments on block 88

0 Comments on block 89

0 Comments on block 90

0 Comments on block 91

0 Comments on block 92

0 Comments on block 93

0 Comments on block 94

0 Comments on block 95

0 Comments on block 96

0 Comments on block 97

0 Comments on block 98

0 Comments on block 99

0 Comments on block 100

0 Comments on block 101

0 Comments on block 102

0 Comments on block 103

0 Comments on block 104

0 Comments on block 105

0 Comments on block 106

0 Comments on block 107

0 Comments on block 108

0 Comments on block 109

0 Comments on block 110

0 Comments on block 111