Sun of the True Thought

The Sun of the True Thought

A Commentary to the

“Treasure House of Higher Knowledge”

root text by:

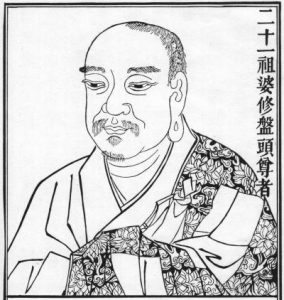

Master Vasubandhu (350ad)

commentary by:

Choney Lama, Drakpa Shedrup (1675-1748)

translated by Stanley Chen

with Geshe Michael Roach

Copyright © 2018 individually by Stanley Chen & Geshe Michael Roach.

All rights reserved.

Sections may be reproduced with the authors’ permission. Please contact:

stanley.chen1357@foxmail.com

Volume 4 of the Classics of Middle Asia Series

Diamond Cutter Press

6490 Arizona Route 179A

Sedona, Arizona 86351

USA

Table of Contents

Translation of the “Sun of the True Thought”……………………………… 5

An offering and a pledge…………………………………………………………………………… 5

The meaning of the front matter……………………………………………………………… 10

The name of the work……………………………………………………………………………… 11

The translator bows down………………………………………………………………………. 12

Vasubandhu’s offering of praise……………………………………………………………… 14

What is darkness?……………………………………………………………………………………. 17

When are we perfectly free of faults?………………………………………………………. 24

What does it mean to degenerate, spiritually?…………………………………………. 25

Is there a difference between misunderstanding, and not knowing?………. 27

Does a disciple of higher knowledge have to have entered a path?…………. 29

Is teaching the only way that a Buddha can help?…………………………………… 31

Has a disciple of higher knowledge already escaped pain?…………………….. 36

Is there anyone that the Teacher refuses to guide?………………………………….. 37

A promise to complete the work……………………………………………………………… 39

What is the ultimate form of higher knowledge?…………………………………….. 40

Are all unstained things higher knowledge?…………………………………………… 42

Is wisdom not the main form of higher knowledge?……………………………….. 43

Is higher knowledge always a state of mind?………………………………………….. 44

Appendices…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 46

Bibliography of works originally written in Sanskrit………………………………. 47

Bibliography of works originally written in Tibetan………………………………. 49

The Sun of the True Thought

[1]

[folio 1a]

*,,CHOS MNGON MDZOD KYI t’IKKA RGYAL BA SRAS BCAS ‘PHAGS TSOGS THAMS CAD KYI DGONGS DON GSAL BAR BYED PA’I NYI MA ZHES BYA BA BZHUGS SO,,

Herein lies The Sun Which Illuminates the True Thought of the Throng of the Realized, All the Able Ones and their Children: A Commentary upon the “Treasure House of Higher Knowledge”

[2]

NA MO GU RU BUDDHA BO DHI SATV’A BHYA:

I bow down to my Lama, the Buddha, and the bodhisattvas.

An offering and a pledge

[3]

,GRANGS MED GSUM GYI TSOGS GNYIS YONGS RDZOGS SKU GSUM GO ‘PHANG MCHOG BRNYES TE,

,RIGS CAN GSUM GYI GDUL BYA’I TSOGS LA RNAM GSUM ‘KHOR LO RAB BSKOR NAS,

,THEG PA GSUM GYI BYANG CHUB LAM BKOD KHAMS GSUM ‘GRO BA’I GNYEN GCIG PU,

,SRID PA GSUM GYI STON PA MCHOG DER SGO GSUM GUS PAS PHYAG ‘TSAL LO,

After collecting good karma

For three countless eons,

You perfected the two collections

And gained that highest state

Of the three holy bodies.

And then you turned the three wheels,

To perfection, for the mass of disciples

Of the three different tracks.

You are the person who set forth

The path to enlightenment

For disciples of all three ways;

You are the one and only real friend

For beings in all three realms.

You are the highest teacher

In all three worlds;

I bow to you with respect

Expressed through all three doors.[1]

[4]

,DRI MED YE SHES SPYAN ZUR GCIG GIS KYANG,

,MA LUS CHOS KYI RANG SPYI’I MTSAN NYID KUN,

,JI BZHIN MA ‘DRES GSAL BAR MNGON GZIGS PA,

,SMRA BA’I DBANG PHYUG ‘JAM PA’I DBYANGS LA ‘DUD,

Your eyes are immaculate wisdom,

And with just a single sidelong glance,

You can see, directly,

All the mental archetypes of things

And all their external expressions,

Without confusing the two in the slightest.

You are the lord of all teachers;

I bow down to you, Gentle Voice.[2]

[5]

,RGYAL BA’I DAM CHOS MA LUS KUN ‘DZIN PAR,

,RGYAL BA NYID KYIS LUNG BSTAN BRNYES GYUR PA,

,RGYAL SRAS THOGS MED SKU MCHED RJES ‘BRANG BCAS,

,RGYAL BA’I GDUNG ‘TSOB DGE BA’I [f. 2a] BSHES SU NGES,

You undertook to preserve

All the teachings of the Victors,

And in fact you attained

The prediction of the Victor.

Surely you are our spiritual friends,

And maintain the line of the Victors;

Brothers Asanga and Vasubandhu,

And all who have come after them,

High children of the Victors.

[6]

,BRTAN PA’I ‘KHOR LO RJE BTZUN TZONG KHA PA,

,PAD DKAR ‘DZIN PA BLO BZANG RGYA MTSO’I SDE,

,YONGS ‘DZIN MKHAS PA NGAG DBANG BRTZON ‘GRUS SOGS,

,DNGOS BRGYUD BLA MA RNAMS LA PHYAG ‘TSAL LO,

You are the steadfast wheel, high and holy Tsongkapa;

You are the holder of the lotus of white, Lobsang Gyatso;

You are the sage of all holy mentors, Ngawang Tsundru;

I bow to all my Lamas, of the present and of the lineage.[3]

[7]

,CHOS MNGON RGYA MTSOR RANG DBANG ‘JUG DKA’ YANG,

,BSHES GNYEN MKHAS PA’I DED DPON LA BRTEN NAS,

,DGONGS DON SNYING PO BSDUS PA’I YID BZHIN NOR,

,LEGS BSHAD RGYAL MTSAN RTZE MOR MCHOD PAR BYA,

It is a difficult thing to set off

Across the ocean of higher knowledge

All on your own.

I was fortunate enough

To find a captain, a sage,

A spiritual guide to take me there.

And I return to you

With the wish-giving jewel

Of the essence of that true thought;

I shall offer it up on the tip of the pole

Of a banner of victory,

In words of eloquence.[4]

The meaning of the front matter

[8]

DE LA ‘DIR MKHAS MCHOG DBYIG GNYEN ZHABS KYIS MDZAD PA’I MNGON PA MDZOD KYI DGONGS DON ‘CHAD PA LA ‘JUG PAR BYA STE,

And so now I shall undertake an explanation of the Treasure House of Higher Knowledge, which was composed by that highest of sages, Vasubandhu.

[9]

DE YANG RTZA BA’I TSIG DON LA NGES PA RNYED PA’I CHED DU RANG RANG GI SKABS KYI RTZA TSIG BKOD NAS DE’I DON RNAMS RIM PA BZHIN DU ‘CHAD PAR BYA’O,,

In order for you, my readers, to gain some certainty about the meaning of all the words of the root text, I will insert that text for you as we reach each different part,[5] explaining the related points as they come up.

[10]

‘DI LA GSUM, KLAD KYI DON DANG, GZHUNG GI DON DANG, MJUG GI DON BSHAD PA’O,,

My explanation has three parts: the meaning of the front matter, the main body of the book, and the conclusion.

[11]

DANG PO LA, MTSAN GYI DON DANG, ‘GYUR GYI [f. 2b] PHYAG BSHAD PA GNYIS,

The explanation of the front matter has two parts: the meaning of the title, and the meaning of the prostration by the Tibetan translator.

[12]

DANG PO LA, BSTAN BCOS ‘DI’I RGYA SKAD KYI MTSAN DANG, DE BOD KYI SKAD DU BSGYUR BA GNYIS,

First I will present the Sanskrit name of this classical commentary, and then I will translate it into Tibetan for you.

The name of the work

[13]

DANG PO NI, RGYA GAR SKAD DU, AA BHI DHARMA KO shA K’A RI K’A ZHES BYA LA,

In the language of India,

This book is called Abhidharma Kosha Karika.

[title]

[14]

GNYIS PA NI, SHES BYA CHOS CAN, BSTAN BCOS ‘DI’I MTSAN BOD KYI SKAD DU BSGYUR TSUL YOD DE, AA BHI NI MNGON PA, DHARMA NI CHOS, KO shA NI MDZOD, K’A RI K’A NI TSIG LE’UR BYAS PA ZHES BYA BAR ‘GYUR BA’I PHYIR,

Consider all the things there are.

There is a way to translate the Sanskrit of this title,

Because—

abhi means higher,

dharma means knowledge,

kosha means treasure house, and

karika means set in verse.

Thus the full title is The Treasure House of Higher Knowledge, Set in Verse.[6]

[15]

SKAD SHAN SBYAR BA LA DGOS PA YOD DE, BSTAN BCOS ‘DI ‘PHAGS YUL GYI MKHAS PA’I GSUNG YIN PAR SHES PA DANG, LEGS SBYAR GYI SKAD LA BAG CHAGS ‘JOG PA’I CHED YIN PA’I PHYIR RO,,

There are two reasons why the original Sanskrit title was included within the Tibetan translation. First, they wanted people to know that this book was the word of a sage from India: the Land of the Realized Ones. Secondly, they wanted to plant a seed in readers’ minds for learning, at some point, the Sanskrit language.

The translator bows down

[16]

GNYIS PA ‘GYUR GYI PHYAG LA, GZHUNG DGOD PA DANG, DON BSHAD PA GNYIS,

That bring us to the translator’s prostration; first I will show where it is in the root text, and then I will explain the meaning of it.

[17]

DANG PO NI, ‘JAM DPAL GZHON NUR GYUR PA LA PHYAG ‘TSAL LO ZHES BYUNG,

Here is the first:

I bow down to Gentle Voice of Glory,

in his youthful form.

[translator’s prostration]

[18]

GNYIS PA NI, SHES BYA CHOS CAN, YUL GANG LA PHYAG ‘TSAL BA LA DGOS PA YOD DE, SGRIB GNYIS KYI RTZUB REG DANG BRAL BAS NA ‘JAM, TSOGS GNYIS KYI DPAL DANG LDAN PAS NA DPAL, NA TSOD LO BCU DRUG LON PA’I NYAMS CAN YIN PAS NA GZHON NUR GYUR PA STE, DE LA PHYAG ‘TSAL BA YIN PA’I PHYIR,

Here is the second:

Consider all the things there are.

There is a reason why the translators[7] are prostrating to this particular being,

Because they are prostrating to the one who fits the name of “Gentle Voice of Glory, in his youthful form”: a divine being who is—

gentle, soft, in that he has removed the roughness of the two obstacles;[8]

glorious, since he possesses the glory of the two collections; and

in a youthful form, with the appearance of a 16-year-old youth.

[19]

DE LTAR PHYAG ‘TSAL BA LA DGOS PA YOD DE, BSTAN BCOS ‘DI SNGON GYI BKAS BCAD LTAR MNGON PA’I SDE SNOD KYI KHONGS SU GTOGS PAR SHES PA’I CHED YIN PA’I PHYIR,

There is a purpose for this particular prostration,

Because it is so that readers can understand—given the decree of the kings of old—that this work is included into the scriptural collection of higher knowledge.[9]

Vasubandhu’s offering of praise

[20]

GNYIS PA LA, BSTAN BCOS LA ‘JUG PA’I YAN LAG DANG, GZHUNG GI DON DNGOS DANG, BSHAD PA MTHAR PHYIN PA’I TSUL GSUM,

Here is our second part from above, on the main body of the book. We proceed in three sections, treating the steps involved in undertaking the composition of the text; the actual content of the work; and its conclusion.

[21]

DANG PO LA, MCHOD PAR BRJOD PA, [f. 3a] BRTZAM PAR DAM BCA’ BA, MNGON PA’I MTSAN DON, BRTZAMS PA’I DGOS PA BSHAD PA BZHI,

The beginning steps that we shall explain are four in number: the traditional offering of praise; the promise to compose the work; the meaning of the name abhidharma, or “higher knowledge”; and the goals behind the composition.

[22]

DANG PO LA GZHUNG DGOD PA DANG, DE’I DON BSHAD PA GNYIS,

For the first of these, we will first provide the corresponding root text; and then explain its meaning.

[23]

DANG PO NI,

,GANG ZHIG KUN LA MUN PA GTAN BCOM ZHING,

,’KHOR BA’I ‘DAM LAS ‘GRO BA DRANGS MDZAD PA,

,DON BZHIN STON PA DE LA PHYAG ‘TSAL

ZHES BYUNG,

I bow down to the one

Who has completely destroyed

The darkness over all things,

And who leads beings

Out of the swamp

Of the cycle of pain:

To that Teacher who teaches them

According to their crux.

[introduction 1a]

[24]

GNYIS PA LA TSIG DON DANG, MTHA’ DPYAD PA GNYIS,

We will cover the meaning in two parts: the meaning of the words, and then an analysis of them.

[25]

DANG PO NI, SLOB DPON DBYIG GNYEN CHOS CAN, KHYOD KYIS BSTAN BCOS ‘DI RTZOM PA’I THOG MAR STON PA SANGS RGYAS GANG ZHIG LA PHYAG ‘TSAL BA’I RGYU MTSAN YOD DE, RANG NYID DAM PA’I SPYOD PA DANG MTHUN PA DANG, BSOD NAMS ‘PHEL BA DANG, BSTAN BCOS RTZOM PA’I BAR CHAD ZHI BA SOGS KYI CHED YIN PA’I PHYIR,

Here is the first.

Consider Master Vasubandhu.

There is a reason why, as he begins to compose his work, he bows down to the one—that Teacher, the Buddha.

First of all, he wants to honor this tradition of the holy ones.

Secondly, he wants to increase his good karma.

Thirdly, he wants to put to rest any obstacles that might prevent him from composing the work.

[26]

SANGS RGYAS DE CHOS CAN, PHUN SUM TSOGS PA GSUM MNGA’ STE, SHES BYA KUN LA RMONGS PA’I NYON MONGS DANG NYON MONGS CAN MA YIN PA’I SGRIB PA’I MUN PA SA BON DANG BCAS PA GTAN NAS BCOM ZHING SPANGS PA’I SPANGS PA PHUN TSOGS DANG,

And consider this Buddha.

He possesses the three kinds of perfection;

Because he possesses, first of all, a pair of perfections. One of these is that he has rid himself perfectly of negative qualities: he has completely destroyed, and rid himself of, the darkness of obstacles—both those which are negative emotions and those which are not involved with such negativities—which make one ignorant about all the knowable things there are.

[27]

DE’I SHUGS KYIS ‘PHANGS PA’I SHES BYA THAMS CAD RTOGS PA’I RTOGS PA PHUN TSOGS GNYIS DANG LDAN ZHING,

And the other—implied by the first—is that he has perfectly realized each and every thing that can be known.

[28]

BRTZE BA’I THUGS KYIS ‘GRO BA RNAMS LA PHAN PA’I DON SKAL BA JI LTA BA BZHIN DU CHOS STON PA‘I SGO NAS BRGAL BAR DKA’ BA’I ‘KHOR BA’I ‘DAM LAS DRANG BAR MDZAD PA‘I ‘PHRIN LAS PHUN SUM TSOGS PA GSUM DANG LDAN PA’I PHYIR,

Third, he possesses the perfection of holy deeds. That is—motivated by thoughts of love—he grants beings the teachings, to aid them, according to their crux; meaning, according to the amount of good karma they already have. And in this way, he leads them out of the swamp of the cycle of pain, a place which is crossed only with great difficulty.

What is darkness?

[29]

GNYIS PA MTHA’ DPYAD PA LA, KHA CIG ,NYON MONGS CAN DANG NYON MONGS [f. 3b] CAN MA YIN PA’I MUN PA SPANGS PA’I SPANGS PA YIN NA, ‘DI’I DNGOS BSTAN GYI SPANGS PA YIN PAS KHYAB ZER NA,

Which brings us to our analysis of Master Vasubandhu’s offering of praise. Someone may begin by making the following claim:

Let’s look at this eradication, where one has rid themselves of both darkness involved with the negative emotions, and darkness which is not. It seems to me that this would always be the kind of eradication which is directly referred to in this verse.

[30]

NYAN RANG DGRA BCOM PA’I RGYUD KYI SPANGS PA CHOS CAN, DER THAL, DE’I PHYIR,

In reply we say,

Well then, let’s consider the eradication of negative qualities found within the mind of an enemy destroyer on the listener track.[10]

Are you saying that it is the kind of eradication referred to directly in this verse?

Why do you say that?[11]

Because it is a type of eradication where one has rid themselves of both darkness involved with the negative emotions, and darkness which is not.

[31]

DER THAL, NYAN RANG DGRA BCOM PAS DE GNYIS SPANGS PA’I PHYIR,

In that case, I disagree that theirs is a type of eradication where one has rid themselves of both darkness involved with the negative emotions, and darkness which is not.

But theirs is so this type of eradication!

Why do you say that?

Because an enemy destroyer on the listener track has rid themselves of both these two kinds of darkness.

[32]

DER THAL, DES NYON MONGS CAN GYI MUN PA SPANGS PA GANG ZHIG ,DE MA YIN PA’I MUN PA SPANGS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that an enemy destroyer on the listener track has done so.

Yes they have! Because (1) they have rid themselves of darkness involved with the negative emotions; and (2) they have also rid themselves of darkness which is not involved with them.

[33]

DANG PO DER THAL, DGRA BCOM PA YIN PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree with the first part of your reason: it’s not true that an enemy destroyer on the listener track has rid themselves of darkness involved with the negative emotions.

And yet the first part of our reason is true, because this person is an enemy destroyer!

[34]

GNYIS PA DER THAL, DES DE ‘DUN PA LA ‘DOD CHAGS DANG BRAL BA’I TSUL GYIS SPANGS YANG, GTAN NAS BCOM PA MA YIN PA’I KHYAD PAR ‘THAD PA’I PHYIR,

Well then, I disagree with the second part of your reason: it is not true that this type of enemy destroyer has rid themselves of darkness which is not involved with negative emotions.

But the second part is true as well, for it is reasonable to make the distinction that—although such as person has rid themselves of that darkness in the sense of being free of wanting the desirable[12]—they have not yet destroyed it completely.

[35]

DER THAL, RANG ‘GREL LAS, KUN LA MUN PA BCOM PAR NI ‘DOD MOD KYI, GTAN NAS NI MA YIN TE, ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree with that.

But that is so the case, because the autocommentary says, “We would admit that they have destroyed the darkness over all things; but they have not done so completely.”[13]

[36]

RTZA BAR ‘DOD NA, MI ‘THAD PAR THAL, DE SPANGS PA PHUN TSOGS MA YIN PA’I PHYIR,

Then I agree to your original statement: The eradication found within the mind of an enemy destroyer on the listener track is the kind of eradication referred to directly in this verse.

And yet that cannot be the case, because it is not a perfect eradication.

[37]

DER THAL, DE SANGS RGYAS KYI RGYUD KYI SPANGS PA MA YIN PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that it is not a perfect eradication of negative qualities.

But it isn’t, because it is not the eradication of negative qualities that exists in the mindstream of an Enlightened Being.

[38]

KHYAB STE, ‘DI’I DNGOS BSTAN GYI SPANGS PA DE LA, SKYE MCHED BCU GNYIS KYI CHOS KUN LA SGRIB PA’I MUN PA GTAN NAS BCOM PA ZHIG DGOS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that—just because something is not the eradication of negative qualities that exists in the mind stream of an Enlightened Being—it cannot be a perfect eradication.

But it is necessarily so, because in order to be the eradication of negative qualities referred to directly in this verse, it must be the complete destruction of the darkness which obscures all existing things of the twelve doors of sense.[14]

[39]

DER THAL, KUN LA MUN PA GTAN BCOM ZHING, ,ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that is the case.

And yet it is, since after all the verse mentions “destroying, completely, the darkness over all things.”

[40]

KHA CIG ,’DI’I DNGOS BSTAN GYI MUN PA YIN NA, MUN PA YIN PAS KHYAB ZER NA,

Someone may come and make the following claim:

If something is the darkness referred to directly in this verse, then it must be darkness.

[41]

DE MI ‘THAD PAR THAL,

And yet that must be incorrect.

Why do you say that?

[42]

DE YIN NA, MUN PA MA YIN PAS KHYAB PA’I PHYIR,

Because if something is the darkness mentioned here, it in fact cannot be darkness.

[43]

DE YIN NA, SGRIB PA YIN DGOS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree.

And yet that is the case, because if something is the darkness mentioned here, it must be a spiritual obstacle or obscuration.

[44]

KHYAB STE, SPYIR MUN PA LA, PHYI’I GZUGS KYIS KHYAB PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that if something is a spiritual obscuration, it cannot be darkness.

And yet it cannot; because generally speaking, if something is darkness, it must be an outer physical thing.

[45]

GZHAN YANG, DE MI ‘THAD PAR THAL,

Not only that, but your position is wrong for another reason.

[46]

‘DIR SGRIB PA GNYIS PO DE LA MUN PA DANG CHOS MTHUN YOD PA’I SGO NAS DE’I MING GIS BTAGS PA TZAM YIN PA’I PHYIR,

That’s because the two obstacles are just given the name “darkness” here as an epithet, since they are analogous to darkness.

[47]

DER THAL, MUN PA DES PHYI’I GZUGS GSAL BAR MTHONG BA LA SGRIB PAR BYED PA BZHIN DU, SGRIB PA GNYIS PO [f. 4a] DES NANG CHOS RNAMS KYI RANG SPYI’I MTSAN NYID MNGON SUM DU MTHONG BA LA SGRIB PAR BYED PAS NA DE LTAR BTAGS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that the two obstacles are analogous to darkness.

And yet they are analogous to the dark. The function of darkness is to obstruct our ability to see outer things clearly. Just so, the function of the two obstacles is to obstruct our ability to see, directly, the general and specific characteristics of inner things.

[48]

GZHAN YANG, SKABS ‘DIR DE GNYIS GANG RUNG SPANGS NA, GTAN NAS SPANGS MI DGOS TE, DE GANG RUNG SPANGS NA SLAR MI SKYE BA’I CHOS CAN DU BYAS NAS SPANGS MI DGOS PA’I PHYIR,

Moreover, the case is—in this context—that if you eliminate either or both of these two, you need not do so completely. That’s because you can eliminate one or both of them, and not necessarily do it in such a way that they cannot grow back.

[49]

DER THAL, NYAMS PA’I CHOS CAN GYI DGRA BCOM PA YOD PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that that’s the case.

And yet it is, because there does exist such a thing as an enemy destroyer of the type that drops down from the state they have achieved.

[50]

DER THAL, DGRA BCOM PA RANG GI ‘BRAS BU LAS NYAMS PA YOD PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree.

But there is such an enemy destroyer, because there is the type that “drops down from the result they have attained.”

[51]

DER THAL, DGRA BCOM DGU LAS NYAMS PA’I CHOS CAN SOGS LNGA RANG GI ‘BRAS BU LAS NYAMS PAR ‘GYUR BA DANG, DGRA BCOM PAR {%BAR} PA BZHI NI RANG GI RIGS LAS NYAMS PAR ‘GYUR BA YOD CING, DANG PO RGYUN ZHUGS RANG GI ‘BRAS BU LAS MI NYAMS PA’I KHYAD PAR ‘THAD PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree.

And yet there are such enemy destroyers, because it is correct to draw distinctions such as nine traditional classifications of enemy destroyers; and the five of them—such as “the type that drops down”—who drop down from the status of having attained that result; and the four types of enemy destroyers in the middle of the list who drop down from their class; and the stream enterer at the beginning of the list who does not drop down from the result they have attained.[15]

[52]

DER THAL, RTZA BAR,

,BZHI NI RIGS LAS LNGA ‘BRAS LAS,

,NYAMS ‘GYUR DANG PO LAS MA YIN,

,ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that those distinctions can be drawn.

And yet they can, because the root text says:

Four drop from their class, and five of them

From their result. No one from the first.

[VI.229-230]

When are we perfectly free of faults?

[53]

KHA CIG ,SKABS ‘DIR SHES SGRIB SPANGS PA’I SPANGS PA DE, SPANGS PA PHUN TSOGS SU ‘DOD PAR THAL, ‘DIR SHES BYA’I GNAS TSUL LEGS PAR MTHONG BA LA SGRIB PA’I SGRIB PA KHAS LEN PA’I PHYIR, ZER NA MA KHYAB,

Suppose someone comes along and makes the claim:

It is so the case that, at the present juncture, an eradication where we have rid ourselves of obstacles to knowledge must be considered a perfect eradication of negative qualities. Because here we accept the idea that an obstacle to knowledge is one that obscures our ability to see, properly, the true nature of all existing things.

We would reply that it’s not necessarily the case that if we did accept that idea of an obstacle to knowledge, we would have to consider an eradication where we have rid ourselves of obstacles to knowledge a perfect kind of eradication.

[54]

‘DOD MI NUS TE, DES SGRIB PA LA SHES SGRIB KYI THA SNYAD MI BYED PA’I PHYIR,

And furthermore we cannot even agree to that idea; for we don’t even refer to that kind of obscuration as an “obstacle to knowledge.”

What does it mean to degenerate, spiritually?

[55]

KHA CIG ,YON TAN DE LAS NYAMS PAR ‘GYUR NA, DE THOB PA LAS NYAMS PAS KHYAB ZER NA,

Someone may come and make the following claim:

If someone drops down from a particular good quality, then they must drop down from its achievement.

[56]

DE MI ‘THAD PAR THAL, ‘DIR NYAMS TSUL LA, YON TAN DE THOB PA DANG, MA THOB PA DANG, THOB KYANG MNGON DU MI BYED PA’I NYER SPYAD LAS NYAMS PA GSUM YOD PA’I PHYIR,

And yet that can’t be correct, because there are three different ways in which a person can drop down from a good quality: (1) from one which they have already achieved; (2) from one that they have not yet achieved; and (3) from one they have achieved but not yet “employed”—meaning not yet manifested.

[57]

DER THAL, GNAS DRUG PA LAS,

,THOB DANG MA THOB NYER SPYAD LAS,

,YONGS NYAMS RNAM PA GSUM ZHES BYA,

,ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree with those three categories.

And yet there do exist these three different ways of dropping down from a good quality, for the sixth chapter says,

Understand the ways they drop down as three:

From achievement, none, employment too.

[VI.233-234]

[58]

GSUM GYI KHYAD PAR [f. 4b] YOD DE, DE GSUM GYI DANG PO SNGAR LTAR YIN LA, YON TAN DE MA THOB NA MA THOB PA LAS NYAMS PA DANG, THOB KYANG MNGON DU MI BYED NA NYER SPYAD LAS NYAMS PAR ‘JOG PA’I PHYIR,

The distinction between these three does exist, for it is established as follows. The first of the three is as we described it before. In the case of dropping down from a good quality without having achieved it, the idea is that we simply haven’t achieved it in the first place. In the case of “dropping down from its employment,” the point is that we have achieved a certain quality but have yet to manifest it.[16]

[59]

PHYI MA DER THAL, STON PA LA ‘GOG SNYOMS THOB KYANG DE MNGON DU MA BYAS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree with the idea of achieving something, but not manifesting it.

And yet there is such a thing; for example, our Teacher has achieved the ability to enter a cessation meditation, but would never manifest it.[17]

[60]

DER THAL, DE SGO LNGA’I DBANG SHES DANG TSOR ‘DU RAGS PA RGYUD LDAN GYI GANG ZAG YIN PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that the Teacher has achieved but not manifested this type of meditation.

And yet he has not, for he is a person who still possesses, within his being, the consciousnesses of the five doors of sense; as well as gross forms of feeling and discrimination.

[61]

‘ON KYANG YON TAN DE MA THOB NA, DE LAS NYAMS PAR MA NGES TE, THOB MA THOB BRTZI BA’I GZHI THOB MKHAN NI GANG ZAG GZHIR BYED PA YIN PA’I PHYIR RO,,

We should note though that, even if one has yet to achieve a certain good quality, it is not definite that we can say they have “dropped down” from it. The basis on which we can decide whether the quality has been achieved or not depends on the person who we take as the one who does the achieving.

Is there a difference between misunderstanding,

and not knowing?

[62]

KHA CIG ,MI SHES PA’I CHOS BZHI PO SGRIB PA YIN PAR THAL, RGYU BZHIS YUL BZHI MTHONG BA LA SGRIB PAR BYED PA’I PHYIR ZER NA

Someone may come and make the following claim:

It must be the case that the four things we don’t know are obstacles, since the four factors act to obscure our ability to see the four objects.[18]

[63]

MA KHYAB,

We would reply that it doesn’t necessarily follow: those four do obscure our ability to see the four objects, but that doesn’t mean that the four things we don’t know are obstacles.

[64]

MA GRUB NA DER THAL,

The reason you’ve given though is itself a true statement: it is true that the four factors act to obscure our ability to see the four objects.

[65]

YUL RING BA’I KHAMS DANG ‘GRO BA DANG, SKYE GNAS DANG RTOGS DKA’ BA LA SGRIB PAR BYED CING, DE BZHIN DU ‘JIG RTEN GYI KHAMS ‘BUM SOGS KYIS BAR DU CHOD PA LTA BU’I YUL DANG, BSKAL PA BRGYA STONG SOGS KYIS BAR DU CHOD PA’I DUS RING BA DANG, SHES BYA’I DBYE BA MTHONG BA LA SGRIB PAR BYED PA’I PHYIR,

Why do you say that?

That’s because these four function to obscure our ability to see:

(1) Faraway realms and kinds of beings, types of rebirth, and other things that are difficult to perceive; as well as

(2) Places such as those separated from us by the space in which a hundred thousand planets lie;

(3) Times that are long away, such as those separated from us by hundreds or thousands of eons; and

(4) The infinite categories of existing things.

[66]

RTZA BAR ‘DOD MI NUS TE, SANGS RGYAS KYI ZAG MED KYI PHUNG PO LNGA’I KHYAD PAR PHRA MO RNAMS SGRIB PA MA YIN PA’I PHYIR,

And we can’t agree to your original idea: that the four things we don’t know are obstacles. The subtle qualities of the five unstained parts of a Buddha,[19] for example, are not themselves obstacles.

Does a disciple of higher knowledge

have to have entered a path?

[67]

KHA CIG ,’DI’I DNGOS BSTAN GYI DRANG ‘OS KYI GDUL BYA LA LAM MA ZHUGS YOD PAR THAL, SKAL LDAN GYI LAM MA ZHUGS YOD PA’I PHYIR, ZER NA

Someone may make the following claim:

There do exist disciples that have not yet entered a path,[20] who are still worthy vessels to be granted this particular teaching directly.

Why do you say that?

Because there are people who have great good karmic seeds, but who have not yet entered a path.

[68]

MA KHYAB,

We would reply that it doesn’t necessarily follow: There are admittedly people with great good karmic seeds who have not yet entered a path, but that doesn’t mean that there are students who haven’t entered a path who are still worthy vessels to be granted this teaching directly.

[69]

RTAGS DER THAL, LAM DU ‘JUG KHA MA YIN NA, SKAL LDAN YIN DGOS PA’I PHYIR,

Your reason though is itself a true statement, because if a person is about to enter one of the paths, then they must be a person with great good karmic seeds.

[70]

‘DOD NA, MI ‘THAD PAR THAL, ‘DI’I DNGOS BSTAN GYI SKAL LDAN LA THAR PA CHA MTHUN RGYUD LA SKYES PA CIG DGOS PA’I PHYIR,

But if you still say that that’s enough for a person to be a worthy vessel for granting this teaching directly, we would have to reply that you are incorrect.

Why do you say that?

Because for a person to be someone with great karmic seeds in the sense of being a worthy vessel for receiving this particular teaching directly, they must be a person who has managed to give birth, within their heart, to the spiritual state which we call “conducive to freedom.”[21]

[71]

DER THAL, GANGS SPEL LAS, SKAL PA {%BA} DANG LDAN PA GANG ZHIG CE NA, THAR PA’I CHA DANG MTHUN PA’I DGE BA’I RTZA BA YONGS SU SMIN PA’O, ,ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR,

Why do you say that?

That is true because Master Purnavardhana has said,

What do we mean when we say “a person with great good karmic seeds?” We are talking about a person who has brought to total ripening the store of virtue which is conducive to freedom.[22]

Is teaching the only way that a Buddha can help?

[72]

KHA CIG ,SANGS RGYAS KYI RDZU ‘PHRUL GYIS GDUL BYA ‘KHOR BA DANG NGAN SONG LAS DRANGS BA {%PA} MED PAR THAL, [f. 5a] DES DE DAG LAS CHOS BSTAN NAS ‘DREN DGOS PA’I PHYIR,

Someone may make another claim:

It must not be true that the Buddha uses his miracle powers to rescue disciples from the cycle of pain, and from the lower births.

Why do you say that?

Because he must rescue them by giving them teachings.

[73]

DER THAL, THUB RNAMS SDIG PA CHU YIS MI ‘KHRU ZHING, ,ZHES PA NAS, CHOS NYID BDEN PA BSTAN PAS GROL BAR ‘GYUR, ,ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR NA SNGA MAR MA KHYAB,

I disagree that this is the case.

But it is the case, because we see in scripture the following lines:

The Able Ones cannot wash away

Our bad deeds using water;

Nor can they banish the pain

Of living beings with a wave of their hand;

Or magically transfer their own understandings

From their hearts into ours.

Only by granting us the teachings,

Only by showing us the truth,

Can they ever make us free.[23]

[74]

‘DOD NA, MI ‘THAD PAR THAL, DES RDZU ‘PHRUL BSTAN NAS DANG DE NGAN SONG LAS THAR BAR BYAS RJES ‘KHOR BA LAS GROL BA YOD PA’I PHYIR,

You may take that position, but we would have to say it’s mistaken.

Why do you say that?

There have for example been cases where Lord Buddha used his powers for miraculous displays and thus led someone out of the lower realms—and later to liberation from the cycle of pain.

[75]

DER THAL, DES RDZU ‘PHRUL LA BRTEN NAS ‘KHOR BA DANG NGAN SONG LAS THAR BAR MDZAD NA, DE TZAM GYI DBANG GIS GROL BAR ‘DOD MI DGOS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that this proves your point.

And yet it does. We cite these cases because—even though it is true that, due to the miracles they display, they can help free people from the cycle of pain, and the lower realms—we don’t have to go further and say that these people were liberated by nothing more than these miraculous displays.

[76]

DER THAL, RANG RGYAL GYIS SGRA MED LUS KYI RNAM ‘GYUR GYI SGO NAS GDUL BYA SMIN PAR BYED NA, SANGS RGYAS KYIS LTA SMOS KYANG CI DGOS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that this kind of thing can happen.

Look, we know that a self-made buddha can bring a disciple to ripening without saying anything at all—simply with a gesture of their hand. If that’s the case, then there’s no need to mention what a Buddha can do.

[77]

DER THAL, SGRA MED KYANG DE DE LTAR SNANG, ,ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that this kind of thing can happen.

And yet it can, for we see the lines:

They indicate these things

Without even making a sound.[24]

[78]

DES NA CHOS STON NA NGAG GIS STON PAS MA KHYAB BO,,

Thus we can say that—when one person grants the teaching to another—it need not be through words.

[79]

KHA CIG ,’DI’I DNGOS BSTAN GYI GDUL BYA SKAL LDAN YIN NA, ‘KHOR BA LAS THAR ZIN PAS KHYAB PAR THAL, DE YIN NA, ‘KHOR BA LAS DRANGS ZIN PAS KHYAB PA’I PHYIR,

Someone may make yet another claim:

If a person is a worthy vessel to grant this teaching directly, then they must already have attained freedom from the cycle of pain.

Why do you say that?

Because this kind of person must have already been led out of the cycle.

[80]

DER THAL, DE YIN NA, DE LAS DRANGS PAS KHYAB PA’I PHYIR, DER THAL, RANG ‘GREL LAS, SKAL BA JI LTA BA BZHIN DU DRANGS SO, ,ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR ZER NA,

I disagree that they have!

And yet they must have, because they must have been led out of here!

Again, I disagree.

And yet they must have, because the autocommentary says: “You have led them out, according to the good karma that they possess.”[25]

[81]

MA KHYAB STE, DE NI ‘KHOR BA’I RGUD PA CI RIGS LAS DRANGS PA’I DON YIN PA’I PHYIR,

The autocommentary does include that line, but it doesn’t prove what you say it does. What that is saying is that a person is led out of certain troubles of cyclic life, according to whatever good karma they may possess.

[82]

DER THAL, JI SKAD DU,

,KHYOD KYIS GANG LAS ‘GRO BA DAG

,MA DRANGS RGUD PA GANG MA MCHIS,

,ZHES GSUNGS PA LTA BU YIN PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that this is what the line means!

And yet that is what it means, for it follows the same thought as these lines:

There is not one of the troubles

That you cannot lead us out of.[26]

Has a disciple of higher knowledge already escaped pain?

[83]

KHA CIG ,’DI’I DNGOS BSTAN GYI DE YIN NA, ‘KHOR BA LAS DRANGS PAS KHYAB PAR THAL, RTZA BAR, ‘KHOR BA’I ‘DAM LAS ‘GRO BA DRANGS MDZAD PA, ,ZHES GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR NA,

Here’s still another claim:

It is so the case that if a person is a worthy vessel to grant this teaching directly, they must have been led out of the cycle of pain.

Why do you say that?

Because, after all, the root text itself says—

. . . Who leads beings

Out of the swamp

Of the cycle of pain…

[introduction 1a]

[84]

RE ZHIG ‘DOD KYANG RUNG STE, ‘DIR DRANG ZHES PA DRANGS ZIN KHO NA’I DON MA YIN PA’I PHYIR,

In a sense, we can agree to your statement; but remember that the word “lead” here doesn’t only apply to those who have already been led.

[85]

DER THAL, DE NI BYA BYED GNYIS KA LA SBYOR [f. 5b] RIGS PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree.

But it is so, because “leads” here can apply both to the act, and to the agent.

[86]

DER THAL, BYED PA LA SBYAR BA’I TSE DRANG BAR MDZAD PA STE ‘DREN PA’I SKABS LA SBYOR RUNG ZHING, BYA BA LA SBYOR BA’I TSE DRANGS ZIN PA LA SBYOR RIGS PA’I PHYIR,

Again, I disagree!

But it can! When we say “it applies to the act,” we can be referring to the Buddha’s act of leading people; and when we say “it applies to the agent,” we can be referring to the Buddha’s already having led people.

Is there anyone that the Teacher refuses to guide?

[87]

KHA CIG ,STON PAS SKAL PA {%BA} DANG MI LDAN PA’I GDUL BYA MI ‘DREN PAR THAL, NYI MA SHAR BA’I TSE YONGS SU SMIN PA’I PADMO KHA ‘BYED NUS SHING, MA SMIN PA’I PADMO KHA MI ‘BYED PA LTAR, SANGS RGYAS ‘JIG RTEN DU BYON YANG GDUL BYA SMIN MA SMIN PA’I DON BYED MI BYED DE DANG ‘DRA BA’I PHYIR,

Now suppose yet another claim is made:

Isn’t it actually the case that our Teacher does not lead those who lack the necessary quantity of good karmic seeds?

Why do you say that?

Because what we’re talking about here is the same as what is referred to when they say, “When the sun comes out, it can open the petals of a lotus which is completely ripe to open; but it cannot open those of a lotus which is not yet ripe.” That is, a Buddha may step into this world, but whether or not they can help a particular disciple depends on whether that person is ripe to help, or not.

[88]

DER THAL, JI SKAD DU,

,JI LTAR NYI MA SHAR BA NA,

,YONGS SMIN PADMA KHA ‘BYED LTAR,

,ZHES SOGS GSUNGS PA’I PHYIR NA,

I disagree!

And yet this is the case, for we see references such as the following:

It’s the same as when

The sun comes out,

And the ripened lotus

Spreads its petals.[27]

[89]

MA KHYAB,

There are indeed references such as the one you’ve presented, but they fail to prove your point.

[90]

‘DOD MI NUS TE, SANGS RGYAS KYIS DON MI BYED PAR YAL BAR DOR BA’I SEMS CAN MED PA’I PHYIR,

In any case we cannot agree with your position, because the fact is that there is not a living creature in the universe whom the Buddhas ever disregard—whom they are not working for, all the time.

[91]

‘ON KYANG SKAL BA DANG LDAN PA’I GDUL BYA ‘DREN PAR DNGOS SU BSTAN PA’I SHUGS LA, SKAL BA DANG MI LDAN PA RNAMS DNGOS SU SMIN PAR MI MDZAD PAR BSTAN TE,

We can however say that—just given the expression “disciples with great good seeds, to whom this teaching is granted directly”—the implication is that there exist other disciples who do not possess these kinds of seeds; and that the Buddhas are for the time being unable to bring them to ripening, directly.

[92]

JI SKAD DU,

,SANGS RGYAS RNAMS NI BYUNG GYUR KYANG,

,SKAL BA MED PAS BZANG MI MYONG,

,ZHES PA LTA BU YIN PA’I PHYIR,

This is reflected in the lines that say,

The Buddhas may make their appearance,

But those who lack sufficient seeds

Will never experience the miracle.[28]

A promise to complete the work

[93]

GNYIS PA NI, NAS, ,CHOS MNGON MDZOD KYI BSTAN BCOS RAB BSHAD BYA, ,ZHES BYUNG,

This brings us to our second step from above: the promise to compose the work. This is found in the root text with the words—

Then shall I write

This classical commentary,

The Treasure House of Higher Knowledge.

[introduction 1b]

[94]

SLOB DPON CHOS CAN, KHYOD KYIS STON PA LA MCHOD BRJOD MDZAD NAS, BYA BA GANG LA ‘JUG PA YOD DE, CHOS MNGON PA SDE BDUN GYI BRJOD BYA’I DON THAMS CAD ‘DUS PA’I RGYAL PO’I BANG MDZOD LTA BU‘I BSTAN BCOS ‘DI RAB TU BSHAD PAR BYA BAR BZHED PA’I PHYIR,

Consider Master Vashubandu.

There is a certain action which he undertakes, now that he has completed his offering of praise to the Teacher;

And this is that he agrees to write this classical commentary, which is similar to the treasure house in which a king stores his riches—in that within it we can find, all stored together, every topic treated by the Seven Books of Higher Knowledge.

What is the ultimate form of higher knowledge?

[95]

GSUM PA LA, DON DAM PA’I CHOS MNGON PA’I DON DANG, BRDAR BTAGS PA’I CHOS MNGON PA’I DON DANG, MDZOD KYI MTSAN DON BSHAD PA GSUM,

Which brings us to the third step we promised before: the meaning of the name, abhidharma—or “higher knowledge.” We proceed in three parts: an explanation of the ultimate form of higher knowledge; of what we just call “higher knowledge”; and of the expression “treasure house.”

[96]

DANG PO NI, CHOS MNGON SHES RAB DRI MED RJES ‘BRANG BCAS, ,ZHES ‘BYUNG,

The first of these is reflected in the root text where it says:

Higher knowledge is unstained wisdom,

Along with its accessories.

[introduction 2]

[97]

‘DI LA TSIG DON DANG, MTHA’ DPYAD PA GNYIS,

We’ll cover this point in two steps of its own: an explanation of the wording, and then an analysis.

[98]

DANG PO NI, MTHONG SGOM MI SLOB LAM DRI MED RJES ‘BRANG DANG BCAS PA CHOS CAN, DON DAM PA’I CHOS MNGON PA YIN TE, [f. 6a] DON DAM PA YIN PA’AM, DE LAS BYUNG ZHING CHOS ‘GOG LAM LA MNGON DU PHYOGS PA’AM MNGON SUM DU RTOGS PAS NA DON DAM PA DANG MNGON PA ZHES BRJOD PA’I PHYIR,

Here is the first:

Let’s consider the three unstained paths—the path of seeing, the path of habituation, and the path of no more learning; along with their accessories.

These are the ultimate form of higher knowledge [abhidharma],

Because, first of all, they are either the ultimate, or they derive from it; and because they bring one on up to [abhi] that high object [dharma] of the end of pain and the path to that end—or else enable us perceive these things directly. Thus we say that they are both ultimate and higher.

[99]

DON DAM PA’I CHOS MNGON PA CHOS CAN, PHUNG PO LNGA PA CAN YIN TE, ZAG MED KYI SHES RAB RJES ‘BRANG STE ‘KHOR DU BYAS PA’I TSOR BA ‘DU SHES ‘DU BYED RNAM SHES DANG BCAS PA’I LNGA PA CAN YIN PA’I PHYIR,

Let’s consider the ultimate form of higher knowledge.

It involves the five parts of a person,

Because it consists of unstained wisdom, along with its accessories—five different parts which include among them the capacity of feeling; the capacity of discrimination; the other factors; and the consciousness that occur in conjunction with this wisdom.

Are all unstained things higher knowledge?

[100]

GNYIS PA MTHA’ DPYAD PA LA,

Here secondly is a dialectical analysis of this topic.

[101]

KHA CIG ,ZAG MED KYI CHOS YIN NA, DON DAM PA’I CHOS MNGON PA YIN PAS KHYAB ZER NA,

Someone may come and make the following claim:

Anything which is an object which is unstained is higher knowledge in its ultimate form.

[102]

NAM MKHA’ CHOS CAN, DER THAL, DE’I PHYIR,

Well then, let’s consider empty space.

Are you saying that this is higher knowledge in its ultimate form?

Why do you say that?

Because it is an object which is unstained.

[103]

DER THAL, ‘DUS MA BYAS GSUM PO GANG RUNG YIN PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that empty space is an object which is unstained.

It is too an unstained object, because it is one of the three types of existing things which were never created.

[104]

DER THAL, CHOS CAN DE YIN PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that it is.

It is too, because it is that object we asked you to consider.

[105]

‘DOD MI NUS TE, LAM BDEN MA YIN PA’I PHYIR,

Then I agree that empty space is higher knowledge in its ultimate form.

And yet you can’t agree, because it is not something included into the truth of the path to the end of pain.

Is wisdom not the main form of higher knowledge?

[106]

KHA CIG ,’DIR CHOS MNGON PA LA SHES RAB GTZO BOR GYUR PA MI ‘THAD PAR THAL, RNAM SHES GTZO BO DANG SHES RAB DE’I ‘KHOR DU ‘BYUNG BA’I PHYIR ZER NA,

Someone else may make yet another claim:

It’s incorrect to say here that wisdom is the principal form of higher knowledge.

Why do you say that?

Because it’s consciousness which is principal; and wisdom only occurs in conjunction with it.

[107]

MA KHYAB,

Of course consciousness is the principal element, and wisdom only occurs in conjunction with it; but that doesn’t prove that it’s incorrect to say, here, that wisdom is the principal form of higher knowledge.

Is higher knowledge always as state of mind?

[108]

KHA CIG ,CHOS MNGON PA YIN NA, SHES PA YIN PAS KHYAB ZER NA,

Supposed another person comes along and makes this claim:

If something is an example of higher knowledge, then it must be a state of mind.

[109]

‘PHAGS RGYUD KYI ZAG MED KYI SDOM PA CHOS CAN, DER THAL, DE’I PHYIR,

Well then, we ask you to consider the unstained self-control[29] in the heart of a realized being.

Are you saying it is a state of mind?

Why do you say that?

Because it is an example of higher knowledge.

[110]

DER THAL, ZAG MED KYI PHUNG PO LNGA PO GANG RUNG YIN PA’I PHYIR,

I disagree that it is!

And yet it is, because it is included into one of the five unstained parts that a person can have.

[111]

DER THAL, CHOS CAN DE YIN PA’I PHYIR,

Again, I disagree!

And yet it is, because it is the very object which we asked you to consider.

[112]

‘DOD NA, MI ‘THAD PAR THAL, GZUGS PHUR {%PHUNG} YIN PA’I PHYIR,

In that case, I agree: The unstained self-control in the heart of a realized being is, indeed, a state of mind.

If you do agree to what we first said, then you are wrong!

Why do you say that?

Because the unstained self-control in the heart of a realized being is included into the part of them which is physical.

To Be Continued!

Appendices

Bibliography of works originally written in Sanskrit

S1

Vasubandhu (Tib: dByig-gnyen), c. 350ad. The Treasure House of Higher Knowledge, Set in Verse (Abhidharmakoṣakārikā) (Tib: Chos mngon-pa’i mdzod kyi tsig-le’ur byas-pa, Tibetan translation at TD04089, ff. 1b-25a of Vol. 2 [Ku] in the Higher Knowledge Section [Abhidharma, mNgon-pa] of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

S2

Vasubandhu (Tib: dByig-gnyen), c. 350ad. An Explanation of the “Treasure House of Higher Knowledge” (Abhidharmakoṣabhāṣya) (Tib: Chos mngon-pa’i mdzod kyi bshad-pa, Tibetan translation at TD04090, ff. 26b-258a of Vol. 2 [Ku] and ff. 1b-95a of Vol. 3 [Khu] in the Higher Knowledge Section [Abhidharma, mNgon-pa] of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

S3

Maitreya (Tib: Byams-pa), as dictated to Asaṅga (Tib: Thogs-med), c. 350ad. The Jewel of Realizations, a Book of Advices upon the Perfection of Wisdom (Abhisamayālaṅkāra Nāma Prajñāpāramitopadeśa Śāstra) (Tib: Shes-rab kyi pha-rol tu phyin-pa’i man-ngag gi bstan-bcos mNgon-par rtogs-pa’i rgyan, Tibetan translation at TD03786, ff. 1b-13a of Vol. 1 [Ka] in the Perfection of Wisdom Section [Prajñāpāramitā, Shes-phyin] of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

S4

Yaśomitra (Tib: Grags-pa’i gshes-gnyen), @. An Explication of the “Treasure House of Higher Knowledge” (Abhidharmakoṣa Ṭīka) (Tib: Chos mngon-pa’i mdzod kyi ‘grel-bshad, Tibetan translation at TD04092, ff. 1b-330a of Vol. 4 [Gu] and ff. 1b-333a of Vol. 5 [Ngu] in the Higher Knowledge Section [Abhidharma, mNgon-pa] of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

S5

Saṃghabhadra (Tib: ‘Dus-bzang), @. A Complete Explanation of that Classical Commentary set in Verse, the “Treasure House of Wisdom” (Abhidharmakoṣa Kārikā Śāstra Bhāṣya) (Tib: Chos mngon-pa mdzod kyi bstan-bcos kyi tsig-le’ur byas-pa’i rnam-par bshad-pa, Tibetan translation at TD04091, ff. 95b-266a of Vol. 3 [Khu] in the Higher Knowledge Section [Abhidharma, mNgon-pa] of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

S6

Vasubandhu (Tib: dByig-gnyen), 350ad. An Explanation of the Divisions of “The First Occurrence in Dependence” (Pratītya Samutpādasyādivibhaṃgayo Nirdeśa) (Tib: rTen cing ‘brel-bar ‘byung-ba dang-po’i rnam-par dbye-ba bshad-pa, Tibetan translation at TD03995, ff. 1b-61a of Vol. 3 [Chi] in the Commentaries to Sutra Section [Sutra Vṛtti, mDo-‘grel] of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

S7

Pūrṇavardhana (Tib: Gang-spel), @. An Explication of the “Treasure House of Higher Knowledge, Set in Verse” (Abhidharma Koṣa Śāstra Kārikā Bhāṣya) (Tib: Chos mngon-pa mdzod kyi bstan-bcos kyi tsig-le’ur byas-pa’i rNam-par bshad-pa, Tibetan translation at TD04093, in two volumes: ff. 1b-347a of Vol. 6 (Cu) and ff. 1b-322a of Vol. 7 (Chu) in the Higher Knowledge Section [Abhidharma, mNgon-pa] of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

S8

Maticitra (Tib: Ma-ti tzi-tra; literally “Blo sna-tsogs”), @. A Praise of That Which is Beyond All Praise, From the Song of Praise to the Conquering Buddha Known as “A Eulogy of All Those Worthy of Honor” (Varṇārhavarṇe Bhagavato Buddhasya Stotre Śakya Stava Nāma) (Tib: Sangs-rgyas bCom-ldan-‘das la bstod-pa bsNgags-par ‘os-pa bsngags-pa las bstod-par mi nus-par bstod-pa, Tibetan translation at TD01138, ff. 84a-100b in Vol. 1 [Ka] in the Collected Eulogies Section [Stotragaṇa, bsTod-tsogs] of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

S9

Śākyamuni Buddha (Tib: Sh’akya thub-pa), 500bc. An Exalted Sutra of the Greater Way entitled “The Cloud of the Jewels” (Ārya Ratna Megha Nāma Mahāyāna Sūtra) (Tib: ‘Phags-pa dKon-mchog sprin ces-bya-ba theg-pa chen-po’i mdo, Tibetan translation at KL00231, ff. 1b-180a of Vol. 18 [Tsa] in the Sutra Section [Sūtra, mDo-mang] of the bKa’-‘gyur [lHa-sa edition]).

S10

Bibliography of works originally written in Tibetan

B1

(Co-ne Bla-ma) Grags-pa bshad-sgrub (1675-1748). The Sun Which Illuminates the True Thought of the Throng of the Realized, All the Able Ones and their Children: A Commentary upon the “Treasure House of Higher Knowledge” (Chos-mngon mdzod kyi t’ikka rGyal-ba sras bcas ‘phags-tsogs thams-cad kyi dgongs-don gsal-bar byed-pa’i nyi-ma, ACIP digital text S00027), 211ff.

B2

(Tse-mchog gling) Yongs-‘dzin Ye-shes rgyal-mtsan (1713-1793). The String of Exquisite Gems, A Supreme Ornament that Beautifies the Teachings of the Victorious Ones: Biographies of the Lamas of the Lineage of the Steps of the Path to Enlightenment (Byang-chub lam gyi rim-pa’i bla-ma brgyud-pa’i rnam-par thar-pa rGyal-bstan mdzes-pa’i rgyan-mchog phul-byung nor-bu’i phreng-ba, S05985), in 2 volumes of 474ff and 498ff.

B3

(Se-ra) rJe-btzun Chos kyi rgyal-mtsan (1469-1546). The String of Golden Beads of Fine Explanation, a Necklace for the Wise: An Analysis of the First Chapter of the “Jewel of Realizations,” and Composed in the Form of Notes to a Teaching by the Good and Glorious Jetsun Chukyi Gyeltsen (sKabs dang-po’i mtha’-dpyod Legs-bshad gser gyi phreng-ba mkhas-pa’i mgul-rgyan zhes-bya-ba rJe-btzun Chos kyi rgyal-mtsan dpal bzang-po’i gsung zin-bris su bkod-pa, ACIP S06815-1), 178ff.

B4

(dGe-bshes) Gro-lung-pa (Blo-gros ‘byung-gnas) (c. 1100ad). An Explanation of the Steps to the Path for Entering into the Precious Teachings of Those Who Have Gone to Bliss (bDe-bar gshegs-pa’i bstan-pa rin-po-che la ‘jug-pa’i lam gyi rim-pa rnam-par bshad-pa) [popular title: The Great Book on the Steps to the Teaching (bsTan-rim chen-mo)], in two parts (ACIP S00070-1 and ACIP S00070-2), folios 1a-295b and folios 296a-548a, respectively.

B5

rGyal-tsab rje (Dar-ma rin-chen) (1364-1432). The Essence of an Ocean of Fine Explanation for Higher Knowledge: An Explication of the “Compendium of All the Teachings on Higher Knowledge” (mNgon-pa kun las btus-pa’i rnam-bshad Legs-par bshad-pa’i chos-mngon rgya-mtso’i snying-po, ACIP S05435), 215ff.

B6

(rGyal-ba) dGe-‘dun grub (1391-1474). Illumination of the Path to Freedom: An Explanation of the Holy Treasure House of Higher Knowledge (Dam-pa’i Chos-mngon-pa mdzod kyi rnam-par bshad-pa Thar-lam gsal-byed, ACIP S05525), 205ff.

B7

(Chos-rje) Ngag-dbang dpal-ldan (b. 1806). “Following a Tradition of Eloquence”: A Word-by-Word Commentary to “Entering the Middle Way” (dBu-ma la ‘jug-pa’i tsig-‘grel Legs-bshad rjes-‘brang), ACIP S00981, 189 ff.

B8

(Bse) Ngag-dbang bkra-shis (1678-1738). Fulfilling the Hopes of the Fortunate: A Necklace for the Wise, a Great Explanation which is Designed for All Three Types of People—those of Highest, Medium, and Lesser Capacity; and which Wraps into it the Meaning of the “Commentary on Correct Perception,” that Great Classical Work which itself Comments on the True Intent of the Teachings on Correct Perception (Tsad-ma’i dgongs-‘grel gyi bstan-bcos chen-po rNam-‘grel gyi don gcig tu dril-ba Blo rab ‘bring tha-ma gsum du ston-pa legs-bshad chen-po mkhas-pa’i mgul-brgyan skal-bzang re-ba kun-skong, ACIP @), 158ff.

B9

(dGe-bshes) ‘Chad-kha-ba (Ye-shes rdo-rje) (1101-1175). Eight Verses of Instruction for Developing a Good Heart, along with a Story about Them (Blo-sbyong tsigs-rkang brgyad-ma lo-rgyus dang bcas-pa, ACIP S00380), section #40 in The Compendium of Instructions for Developing a Good Heart, compiled by the Great Bodhisattva Konchok Gyeltsen (Sems-dpa’ chen-po dKon-mchog rgyal-mtsan gyis phyogs-bsgrigs mdzad-pa’i blo-sbyong brgya-rtza, ACIP S06969), 581pp.

B10

(Zhu-chen) Tsul-khrims rin-chen (fl. 1730). A Catalog to the Tengyur, Derge Edition (bsTan-‘gyur dkar-chag, sDe-dge par-ma, ACIP TD04569), ff. 337-468 of Vol. Shr’i of the bsTan-‘gyur [sDe-dge edition]).

B11

(Paṇ-chen) Blo-bzang chos kyi rgyal-mtsan (1565-1662). “The Explication of the First Chapter,” Part of “The Ocean of Fine Explanation, which Clarifies the Essence of the Essence of the ‘Ornament of Realizations,’ a Classical Commentary of Advices on the Perfection of Wisdom” (Shes-rab kyi pha-rol tu phyin-pa’i man-ngag gi bstan-bcos mNgon-par rtogs-pa’i rgyan gyi snying-po’i snying-po gsal-bar legs-par bshad-pa’i rgya-mtso las skabs dang-po’i rnam-par bshad-pa, ACIP S05942), 41ff.

B12

Se-ra rje-btzun Blo-bzang chos kyi rgyal-mtsan (1469-1546). The Excellent Explanation, a Sea of Sport for Those Fortunate Lords of the Serpentines, Written in Clarification of Difficult Points found in the Two Treatises upon the “Ornament of Realizations” (bsTan-bcos mNgon-par rtogs-pa’i rgyan ‘grel-pa dang bcas-pa’i rnam-bshad rnam-pa gnyis kyi dka’-ba’i gnad gsal-bar byed-pa Legs-bshad skal-bzang klu-dbang gi rol-mtso, ACIP S06814, in 11 volumes, with following pagination: Vol. 1 (on first part of Chapter 1), 165ff (but input incomplete); Vol. 2 (on second part of Chapter 1), 45ff; Vol 3 (on the path of preparation), 28ff; Vol. 4 (on the attainment of armor and further topics, incomplete); Vol. 5 (on Ch. 2, incomplete); Vol. 6 (on Ch. 3), 25ff; Vol. 7 (on Ch. 4, incomplete); Vol. 8 (on Ch. 5), 37ff; Vol. 9 (on Ch. 6), 5ff; Vol. 10 (on Ch. 7), 7ff; Vol 11 (on Ch. 8), 67ff.

B13

Se-ra rje-btzun Blo-bzang chos kyi rgyal-mtsan (1469-1546). A Necklace for Master Scholars: A Presentation on the Levels and Paths by the Good and Glorious One, the Holy Chukyi Gyeltsen (rJe-btzun Chos kyi rgyal-mtsan dpal bzang-po’i gsung mKhas-pa’i mgul-rgyan ces-bya-ba Sa-lam rnam-gzhag, ACIP S06826), 20ff.

B14

(Gung-thang) dKon-mchog bstan-pa’i sgron-me (1762-1823). The Entry Point for Amazing Miracles: A Commentary to “The String of Pure Mountains of Snow,” Lines of Praise Related to How Our Lord and Lama, Je Tsongkapa, Reached the State of Enlightenment (rJe Bla-ma mngon-par ‘tsang-rgya ba’i-tsul dang ‘brel-bar bsTod-pa rnam-dag gangs-ri-ma’i ‘grel-pa rMad-byung bkod-pa’i ‘jug-ngogs, ACIP S00953), 21ff.

[1] All three doors: Choney Lama is playing with ones, twos, and threes, some of which need some explaining. The three “countless” eons actually do have a count: three trillion trillion trillion trillion trillion—which is the traditional period it takes to reach enlightenment after we have achieved bodhichitta, the wish for enlightenment (itself a high accomplishment). See for example Biographies of the Lamas of the Steps of the Path, by Yongdzin Yeshe Gyeltsen (1713-1793), Vol. 1, f. 10a (%B2, S05985); and Master Vasubandhu’s own commentary to his Treasure House, at ff. 157b-158b of Vol. 1 (%S2, TD04090).

The “two collections” are those of merit and wisdom: vast masses of good deeds which produce, respectively, the physical and mental bodies of a Buddha. These bodies are also counted as “three”: the paradise body, or form of an Enlightened Being within their own heaven; the emanation body, the form that a Buddha takes to appear on different worlds to help different people; and the reality body, consisting of the omniscient mind of a Buddha, and their ultimate reality.

The “three turnings of the wheel” are the three distinct periods during which Lord Buddha taught, in his lifetime. They are named from their main subject matter: the Wheel of the Four Truths (during which he taught that things have some nature of their own); the Wheel of Nothingness (during which he taught that nothing has any nature of its own); and the Wheel of Fine Distinctions (during which he qualified his former positions on a self-nature). See for example the fine presentation by Sera Jetsun Chukyi Gyaltsen (1469-1546) in the first volume of his dialectic analysis of the Jewel of Realizations (%B3, S06815-1, ff. 38b-39a).

The “three tracks” are three approaches for attaining nirvana and Buddhahood: that of the listeners, who can listen to the highest track, and repeat it to others, but not follow it themselves; the self-made buddhas, who are not full Buddhas but attain nirvana without following a teacher in this life (although they have had countless teachers in their past lives); and the bodhisattvas of the supreme track, who act out of a desire to reach enlightenment for all living beings. For respective explanations see the classic Great Book on the Steps of the Teaching by Geshe Drolungpa (c. 1100ad), f. 374b, Volume 2 (%B4, S00070-2); the commentary to Master Asanga’s Compendium of Higher Knowledge by Gyaltsab Je (1364-1432) (f. 194a, %B5, S05435); and the classic definition of bodhichitta in Lord Maitreya’s Jewel of Realizations (f. 2b, %S3, TD03786).

The “three ways” are the lower way, where a person works for their own enlightenment only; the higher way which is open, where a person works towards the ability to achieve the good of all beings for as many eons as it takes; and the higher way which is secret—also called the Diamond Way, which requires only one lifetime.

The “three realms” are the three divisions of the universe: the desire realm, where people are primarily motivated by a desire for food and sex; the form realm, where beings are distinguished by an exquisite bodily form; and the formless realm, where beings have a nearly purely mental body, with no physical form. See for example the commentary to the Treasure House by Gyalwa Gendun Drup (1391-1474), ff. 74a-74b (%B6, S05525).

The “three worlds” here refer to the area below the earth; upon the earth; and above the earth. For one reference see f. 183b of the commentary to Entering the Middle Way by the great Mongol sage Kalka Ngawang Pelden (b. 1806) (%B7, S00981). The “three doors” are the three ways of expressing ourselves: through our actions; words; and thoughts.

[2] Mental archetypes and external expressions: A particularly popular concept with the Sutrist School of ancient India, where unchanging mental images are reflected in external concrete objects: for example, the perfect concept of a water pitcher, and the water pitcher on the table right now. See for example the entire section starting at f. 118a of Fulfilling the Hopes of the Fortunate, by Ngawang Tashi (1678-1738) (%B8, S00217). “Gentle Voice” refers to the enlightened embodiment of wisdom, Manjushri.

[3] All my Lamas: “Steadfast Wheel” (Skt: Sthira Chakra) is an epithet of Manjushri, the divine tutor of Tsongkapa, with whom he is identified. “Holder of the White Lotus” is another name for the divine embodiment of compassion, Loving Eyes (Skt: Avalokiteshvara, Tib: Chenresik), with whom the Dalai Lamas are traditionally identified; Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (1617-1682) was the “Great Fifth” of this line. Jamyang Shepa Ngawang Tsundru (1648-1721) is a distinguished precursor from the Gomang College of Drepung Monastery—and all are lineage teachers of Choney Lama.

[4] Words of eloquence: In the customary pledge to compose his text, Choney Lama refers to the ancient Indian tradition of going to the source of gemstones—the ocean—for a wishing jewel (Skt: chintamani). This magic stone will grant all your wishes if on the full moon you wash it in perfumed water; set it atop the finial of a victory banner; and present offerings before it. A good scriptural source for this process is to be found in the commentary to the famous Eight Verses on Developing the Good Heart composed by Geshe Chekawa Yeshe Dorje (1101-1175) (p. 207, %B9, S00380).

[5] Insert the root text: In our translation here, the root text will be indicated in bold text, along with the chapter and line numbers in square braces. Where Choney Lama has woven the words of Master Vasubandhu’s root text into his commentary, these words will be italicized.

[6] There is a way: Choney Lama here utilizes the classical form of a logical argument, to give his text a debate-ground flavor. He will be doing this throughout the text.

[7] Why the translators are prostrating: The translators of the Treasure House from Sanskrit to Tibetan, incidentally, are listed in the native catalog to the Derge edition of the Tengyur as the Indian sage Jinamitra and the Tibetan master translator and editor, Peltsek Rakshita; both from the 8th century. See ff. 448a-448b of this wonderful index (%B10, ACIP TD04569).

[8] Two obstacles: That is, obstacles to attaining nirvana (the permanent ending of negative emotions), and obstacles to attaining full enlightenment.

[9] The decree of the kings of old: This decree is described as follows by His Holiness the First Panchen Lama, Lobsang Chukyi Gyeltsen (1570-1662): “The kings, royal ministers, and sages of old decreed that at the beginning of a work belonging to the scriptural section on vowed morality, the translator should bow down to omniscience; and at the beginning of a work belonging to the section on higher knowledge, to glorious Gentle Voice; and at the beginning of a work belonging to the section on the classics, to the Buddhas and bodhisattvas.” See f. 9a of his “Explication of the First Chapter,” Part of “The Ocean of Fine Explanation, which Clarifies the Essence of the Essence of the ‘Ornament of Realizations,’ a Classical Commentary of Advices on the Perfection of Wisdom,” (entry %B11, ACIP S05942).

[10] Enemy destroyer on the listener track: Meaning a person who has permanently rid themselves of the enemy of negative emotions, and thus reached nirvana; but who is still at the point where they can only listen to the teachings about reaching total enlightenment for the sake of all beings, and not yet practice these teachings in their own life.

[11] Why do you say that? In sections of Choney Lama’s text which are written in debate format, we will supply in italics lines such as this one, where they are assumed in the traditional process of formal argument—although not necessarily written down in the text itself.

[12] Wanting the desirable: A technical term from the abhidharma (Tib: ‘dun-pa la ‘dod-chags) spelled in different variations, and little explained in the Tibetan tradition. Our translation is based on Master Sanghabhadra’s commentary to the Treasure House (%S5, TD04091, f. 205b), where this is said to prevent one from moving beyond the desire realm; and on Master Yashomitra (%S4, TD04092, Vol. 1, f. 289b), where the translation would be more like “wanting, then desiring,” since he here defines “wanting” as happening before we obtain something desirable; and “desiring” as a feeling about something we have already obtained. Yashomitra earlier on states that “As for what is not involved with negative thoughts, we say that they eliminate the desire of wanting—which is an expression that denotes severing the tie of the negative thoughts that focus on a particular object” (%S4, TD04092, f. 72b). Master Vasubandhu often uses similar language in his commentary to the Sutra on Dependence (%S6, TD03995).

[13] But not completely: See f. 26b of the first volume of Vasubandhu’s autocommentary to the Treasure House (%S2, TD04090).

[14] All existing things of the twelve doors of sense: Another way of saying all existing things in the universe, since these twelve include all six inner organs of sense (eye; ear; nose; tongue; body—as the sensor of tangibles; and thought, counted along with the separate consciousnesses they engender) and all six “outer” objects (visible objects, sounds, smells, tastes, tangibles, and all things as the object of the thought). These twelve are a primary topic of the first chapter of the Treasure House.

[15] Nine classifications of enemy destroyers: These points will be discussed in the sixth chapter below, with lines 221-230 devoted to those who degenerate. Please note that we will be referencing Master Vasubandhu’s root text internally by English line number (which corresponds closely to the Tibetan line number) rather than by Sanskrit or Tibetan verse number, as this is more precise in the present translation, and more useful for the reader. The Sanskrit verse or shloka can normally be obtained by dividing by 4; thus, a reader interested in referencing the Sanskrit could check for this reference around the 57th verse of Chapter 6; and this is in fact the correct verse.

[16] Yet to manifest it: A word of advice to our readers. Many of the teachings of the abhidharma, such as those here, may at first sight seem dry and pedantic; but they have survived for thousands of years because they force us to think more deeply about deep spiritual truths. So just relax, surrender to the difficulty, and find an application to your real life: this is the goal. Here, for example, do you think there is any good quality that you are actually capable of, yet have not bothered to manifest in your day-to-day life? And isn’t that preferable to not possessing that quality in the first place, because you are incapable of it?

[17] A cessation meditation: A type of meditation where we nearly shut down the mind—not always a desirable goal. It will be discussed in Chapter 2; at lines 170-176 and 190-194. Another word of advice to our reader: It’s a conundrum of these ancient commentaries that they present arguments which utilize concepts which we haven’t reached yet. Get used to it, it’s a nice ah-ha moment later, when you do get to the section that was used to prove something earlier.

[18] Four factors: Mentioned immediately following; a nice, detailed presentation of the four is found in the treatment of this same section of Master Vasubandhu’s root text by Gyalwa Gendun Drup; see the section starting at f. 4a of his commentary to the Treasure House (%B6, S05525).

[19] Five unstained parts of a Buddha: The idea of a “stain,” and things which are free of this impurity, is central to the teachings on higher knowledge, and will be covered in detail soon below; as will the five parts of a person.

[20] Not yet entered a path: Buddhism charts five different stages in our spiritual development, each one known as a “path.” These will be discussed in Chapter 6, “The Path and the Practitioner”

[21] Conducive to a part of freedom: This is a phrase used to describe the first of the five paths, or stages in our spiritual development. This first path is called the “path of accumulation” because, as the great sage Sera Jetsun Chukyi Gyeltsen (1469-1546) notes, “this is the first of the paths on which we are accumulating good karma to freedom” (see f. 60b of %B12, S06814-4).

It is conducive [Skt: bhāgīya, Tib: cha-mthun] to freedom [Skt: mokṣa, Tib: thar-pa] because, as the same author notes, “Freedom we describe as the truth of the end of pain, where we have gotten rid of the obstacles to nirvana. A part [cha] of this freedom is the truth of the end of pain where we have gotten rid of obstacles to nirvana which are learned, [as opposed to inborn]. And this path represents a point in our spiritual life which is conducive [rjes-su mthun-pa] to achieving that part” (see f. 16a, %B13, S06826).

[22] The store of virtue: See f. 9b of his wonderful commentary to the Treasure House (%S7, TD04093-1).

[23] Only by showing us the truth: Choney Lama is referring to the verse as it appears for example in Je Tsongkapa’s Entry Point for Amazing Miracles (see ff. 4b-5a, %B14, S00953). Since it is well known to his readers, Choney Lama quotes only the first and last lines; we have supplied here the two intervening lines, which are: ,’gro-ba’i sdug-bsngal phyag gis mi sel la, / ,nyid kyi rtogs-pa gzhan la ‘pho min te,. Although the idea that the Buddha cannot for example wash away our mistakes with water is repeated a number of times in the ancient Indian scriptures, the source for the verse as it stands today seems to be the one, with minor differences, found in a famed work entitled A Compendium of Advices Granted for Specific Purposes (see f. 72b, %S@, TD04099).

[24] Without even making a sound: A reference to self-made Buddhas of the “rhinoceros” type, from the famed Jewel of Realizations, by Lord Maitreya and Arya Asanga; they are so named because, like a rhinoceros, they prefer to carry out their practice alone, away from crowds of other people (see f. 5a of %S3, TD03786). For a nice description of the rhino see Sera Jetsun at f. 30b of %B12, S06814-5.

[25] According to their good karma: See f. 95b of the autocommentary, at %S5, TD04091.

[26] Not one of the troubles: See ff. 94a-94b of A Praise of That Which is Beyond All Praise, at %S8, TD01138).

[27] The lotus spreads its petals: See f. 9b of the second volume of Master Purnavardhana’s commentary, at %S@, TD04061. The next two lines of the Tibetan, incidentally, are ,de bzhin de bzhin gshegs byung yang, / ,bsam pa yongs smin kho na sbyong,—meaning:

Those Gone Thus

May make their appearance,

But only those fully ripe

Will be purified.

For an extended presentation of this metaphor in an original sutra, see ff. 87b-89a of the Cloud of Jewels (%S9, KL00231).

[28] Never experience the miracle: From Lord Maitreya’s famed Jewel of Realizations (f. 11b, %S@, TD03786), and often quoted in the centuries since.

[29] Unstained self-control: This concept will be discussed in Chapter 4, which is devoted to a presentation of karma. Suffice here to say that, at certain levels of meditation and realization, we are no longer capable of certain negative deeds; and the negative deeds in question relate primarily to those which are physical, carried out either in our actions or words.

Comments

0 Comments on the whole Page

Login to leave a comment on the whole Page

0 Comments on block 1

Login to leave a comment on block 1

0 Comments on block 2

Login to leave a comment on block 2

0 Comments on block 3

Login to leave a comment on block 3

0 Comments on block 4

Login to leave a comment on block 4

0 Comments on block 5

Login to leave a comment on block 5

0 Comments on block 6

Login to leave a comment on block 6

0 Comments on block 7

Login to leave a comment on block 7

0 Comments on block 8

Login to leave a comment on block 8

0 Comments on block 9

Login to leave a comment on block 9

0 Comments on block 10

Login to leave a comment on block 10

0 Comments on block 11

Login to leave a comment on block 11

0 Comments on block 12

Login to leave a comment on block 12

0 Comments on block 13

Login to leave a comment on block 13

0 Comments on block 14

Login to leave a comment on block 14

0 Comments on block 15

Login to leave a comment on block 15

0 Comments on block 16

Login to leave a comment on block 16

0 Comments on block 17

Login to leave a comment on block 17

0 Comments on block 18

Login to leave a comment on block 18

0 Comments on block 19

Login to leave a comment on block 19

0 Comments on block 20

Login to leave a comment on block 20

0 Comments on block 21

Login to leave a comment on block 21

0 Comments on block 22

Login to leave a comment on block 22

0 Comments on block 23

Login to leave a comment on block 23

0 Comments on block 24

Login to leave a comment on block 24

0 Comments on block 25

Login to leave a comment on block 25

0 Comments on block 26

Login to leave a comment on block 26

0 Comments on block 27

Login to leave a comment on block 27

0 Comments on block 28

Login to leave a comment on block 28

0 Comments on block 29

Login to leave a comment on block 29

0 Comments on block 30

Login to leave a comment on block 30

0 Comments on block 31

Login to leave a comment on block 31

0 Comments on block 32

Login to leave a comment on block 32

0 Comments on block 33

Login to leave a comment on block 33

0 Comments on block 34

Login to leave a comment on block 34

0 Comments on block 35

Login to leave a comment on block 35

0 Comments on block 36

Login to leave a comment on block 36

0 Comments on block 37

Login to leave a comment on block 37

0 Comments on block 38

Login to leave a comment on block 38

0 Comments on block 39

Login to leave a comment on block 39

0 Comments on block 40

Login to leave a comment on block 40

0 Comments on block 41

Login to leave a comment on block 41

0 Comments on block 42

Login to leave a comment on block 42

0 Comments on block 43

Login to leave a comment on block 43

0 Comments on block 44

Login to leave a comment on block 44

0 Comments on block 45

Login to leave a comment on block 45

0 Comments on block 46

Login to leave a comment on block 46

0 Comments on block 47

Login to leave a comment on block 47

0 Comments on block 48

Login to leave a comment on block 48

0 Comments on block 49

Login to leave a comment on block 49

0 Comments on block 50

Login to leave a comment on block 50

0 Comments on block 51

Login to leave a comment on block 51

0 Comments on block 52

Login to leave a comment on block 52

0 Comments on block 53

Login to leave a comment on block 53

0 Comments on block 54

Login to leave a comment on block 54

0 Comments on block 55

Login to leave a comment on block 55

0 Comments on block 56

Login to leave a comment on block 56

0 Comments on block 57

Login to leave a comment on block 57

0 Comments on block 58

Login to leave a comment on block 58

0 Comments on block 59

Login to leave a comment on block 59

0 Comments on block 60

Login to leave a comment on block 60

0 Comments on block 61

Login to leave a comment on block 61

0 Comments on block 62

Login to leave a comment on block 62

0 Comments on block 63

Login to leave a comment on block 63

0 Comments on block 64

Login to leave a comment on block 64

0 Comments on block 65

Login to leave a comment on block 65

0 Comments on block 66

Login to leave a comment on block 66

0 Comments on block 67

Login to leave a comment on block 67

0 Comments on block 68

Login to leave a comment on block 68

0 Comments on block 69

Login to leave a comment on block 69

0 Comments on block 70

Login to leave a comment on block 70

0 Comments on block 71

Login to leave a comment on block 71

0 Comments on block 72

Login to leave a comment on block 72

0 Comments on block 73

Login to leave a comment on block 73

0 Comments on block 74

Login to leave a comment on block 74

0 Comments on block 75

Login to leave a comment on block 75

0 Comments on block 76

Login to leave a comment on block 76

0 Comments on block 77

Login to leave a comment on block 77

0 Comments on block 78

Login to leave a comment on block 78

0 Comments on block 79

Login to leave a comment on block 79

0 Comments on block 80

Login to leave a comment on block 80

0 Comments on block 81

Login to leave a comment on block 81

0 Comments on block 82

Login to leave a comment on block 82

0 Comments on block 83

Login to leave a comment on block 83

0 Comments on block 84

Login to leave a comment on block 84

0 Comments on block 85

Login to leave a comment on block 85

0 Comments on block 86

Login to leave a comment on block 86

0 Comments on block 87

Login to leave a comment on block 87

0 Comments on block 88

Login to leave a comment on block 88

0 Comments on block 89

Login to leave a comment on block 89

0 Comments on block 90

Login to leave a comment on block 90

0 Comments on block 91

Login to leave a comment on block 91

0 Comments on block 92

Login to leave a comment on block 92

0 Comments on block 93

Login to leave a comment on block 93

0 Comments on block 94

Login to leave a comment on block 94

0 Comments on block 95

Login to leave a comment on block 95

0 Comments on block 96

Login to leave a comment on block 96

0 Comments on block 97

Login to leave a comment on block 97

0 Comments on block 98

Login to leave a comment on block 98

0 Comments on block 99

Login to leave a comment on block 99

0 Comments on block 100

Login to leave a comment on block 100

0 Comments on block 101

Login to leave a comment on block 101

0 Comments on block 102

Login to leave a comment on block 102

0 Comments on block 103

Login to leave a comment on block 103

0 Comments on block 104

Login to leave a comment on block 104

0 Comments on block 105

Login to leave a comment on block 105

0 Comments on block 106

Login to leave a comment on block 106

0 Comments on block 107

Login to leave a comment on block 107

0 Comments on block 108